Cedar Gallery

Home

|

Cedar info |

News |

Contact |

![]() Dutch

Dutch

Baba Yaga, Ivan Bilibin

Telling stories (and listening to

them) is probably the oldest form of entertainment known to man.

On our travels we noticed that in many countries there is still a

vibrant tradition of storytelling.

Folktales and narratives remain

a source of fascination in many cultures.

My section, 'Russian stories', will consist largely of my own experiences while travelling through Russia, in addition to interesting local folklore: Russian fairy tales with illustrations by some of my favorite Russian artists, Ivan Bilibin and Victor Vasnetsov.

Enjoy reading, and

please

let me know what you think of the stories. Any help offered to keep the

site going would be welcome!

A.W. March 2019

Photo's: Cees & Aly Wagenvoorde

©PAM PHOTOS Delden

©.All Rights Reserved. NO!- Neither Facebook and

Instagram nor any other visitor may use my name or any of my content

without my permission.

You can contact me at

cedars@live.nl

Subjects

Abramtsevo - Baba Yaga (fairy tale) - by train - Morozko (fairy tale) - Moscow I - Moscow, history of a cathedral - Sergiev Posad I - Sergiev Posad II - Snow maiden (fairy tale)

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - -

Moscow (1), Aug. 2008

Now, everyone in Russia is preoccupied with Vladimir Putin. But to equate this vast empire and it’s rich culture and glorious past with one man, would be a complete misunderstanding of the Russian psyche. Russia is much more than Vladimir Putin. Russia has enriched the world with, among other things, great master pieces in the fields of music, literature, and art, including such great minds as Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Tolstoy, and Tchaikovsky, to name only a very few. So, to identify Russia with Putin would be a gross injustice to this magnificent country.

Russia has always had great and powerful leaders

however. After the tsars came the Communist leaders.

In 2008 we met the

two most famous of these near Red Square. The first was Vladimir Ilyich

Lenin (1870-1924), who seized power in 1917. He actually wanted to

improve the lives of small farmers and workers; but tolerated little

dissention, coming down with an iron fist on those who challenged him.

The other was Joseph Stalin (1879-1953). Stalin took over the country in

1924. Here in the west, he has a reputation as a brutal dictator,

because of the horrors he visited on his people. During his reign

millions were murdered. I must add though, that not every Russian would

concur with our assessment of Stalin.

On this nice day in August we heard no complaints from Lenin and Stalin as they stoically stood overlooking the throngs of visitors who came to see them.

(Music: (Tchaikovsky - The Nutcracker or Swan Lake; Rimski Korsakov - Shéhérazade)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * T O P * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Moscow - history of a cathedral

Other times

In 1838 the construction of the Christ the Savior Cathedral in Moscow began. This cathedral was built to commemorate the Russian victory over Napoleon's Grande Armée. When it was built, it was the largest orthodox church in the world. This cathedral, where almost half a ton of gold was used to adorn it’s interior, as well as precious gems, offered a place to worship for tens of thousands of believers.

But times can, and do, change.

In 1931 Stalin had the church destroyed in order to

build the gigantic Palace of the Soviets in its place. It was to become a

more than 300m high tower, with a 100m high statue of Lenin on top.

However, the new symbol of Communist rule was never constructed on this

ancient foundation.

Instead secretary Nikita Khrushchev (1894-1971) had an open-air swimming

pool built on the location, in the 1950’s. This bath was very popular

amongst the people of Moscow. Unfortunately, as a result of being

heated, volatiles were generated that negatively affected the

neighbouring art collection of the Pushkin Museum; and when it became

evident that necessary repairs, to correct the problem, could not be

carried out, the swimming pool was closed, in 1993.

So what became of this site?

Plans to reconstruct the cathedral in the 1990s were not embraced by everyone. It was seen as a prestigious, but frivolous project, costing millions of rubles, money that could be spent in better ways. People were told that the reconstruction would not be financed out of general funds; but in the end that was exactly what happened. This did not go down well with poverty stricken Muscovites, and considerable resistance ensued.

In the end, the Savior Cathedral rises like a phoenix

from the ashes.

The history of the Christ the Savior Cathedral stands as silent testament to

Russia’s authoritarian tradition.

Putin has, of course, adopted some of the practices of the former Soviet

leaders; but, as can be seen from the story surrounding the previously

mentioned cathedral, Putin, in a religious sense, bears more

resemblance to the tsars than to his predecessors; and what

distinguishes him from them is his close relationship to the Russian

Orthodox Church.

The statue of Tsar Alexander II (1818-1881) is

located in a small garden opposite the Cathedral of Christ the Savior.

This tsar seems to have been present at the official opening of the

original church.

The government in Moscow reserved 60 million rubles for both the design

and execution of the work, as well as the furnishing of the area around

the statue.

In 1990, Alexius II was declared patriarch of Moscow (and all of Russia)

and put in charge of about 100 million believers.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, under the leadership of Alexius II,

support for the Russian Orthodox Church grew stronger among the Russian

population.

In the West, not everyone was enthusiastic about his leadership. He

criticized tolerance toward homosexual behaviour, and characterized

homosexual demonstrations as campaigns promoting immoral behaviour.

Patriarch Alexius II performed the dedication of the monument to

Alexander II in 2005.

Two colossal lions stand guard on either side of this statue. The image itself stands on a black base supported by a semi-circular arch with four columns. The plaque at the foot of the statue refers to 1861, the year in which Tsar Alexander II ended serfdom. The inscription states, he 'freed millions of peasants from centuries of slavery'.

In addition to some other glorifying text, the year 1881 is mentioned. This is the year in which Alexander II was murdered.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * T O P * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Saint Sergius (born around 1314) lived in seclusion

after he was 23 years old.

His parents had died, and his brother (a monk) found a remote place for

him to live, since he did not want to live in a monastery.

Sergius led an ascetic’s life and filled his time with work and prayer.

His brother and he built a small cell and a church dedicated to the

Trinity, deep in the woods. After some time his brother left for a

monastery in Moscow and Sergius was left alone. He dedicated his whole

life to the glory of God.

It wasn’t long before other monks came to visit, asking him to be their

leader. Farmers and citizens also came to receive his blessing and seek

his advice.

He’s a fascinating character, not only for what he accomplished, but as an inspiration. Stories like his abound throughout various cultures all over the world. These aesthetics invariably live quite contemplative lives of seclusion; and their interactions with the outside world are restricted. Yet, or more precisely because of this, they serve as examples to monks and laymen on how to live.

Where Sergius lived the number of monks continued to grow; and not far from there, a posad arose that would develop into the city of Sergiev Posad.

We visited the beautiful Sergiev Posad, about

70 km north of Moscow, in 2016. It is one of the cities on the so-called Golden

Ring.

The city is best known for the Troitse-Sergieva Lavra, the monastery

that was founded here in the 14th century by St. Sergius of Radonezh.

This monastery is one of the largest and most important ones in the

country. Hence the title 'lavra'.

It is a huge complex with very beautiful buildings.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

A POSAD was a settlement

in the Russian Empire, often surrounded by ramparts (defensive walls, to

protect the settlement from potential aggressors) and a moat (a deep,

broad ditch, surrounding the settlement), adjoining a town or a kremlin,

but outside of it, or adjoining a monastery in the 10th to 15th

centuries.

Some posads developed into towns, such as Sergiev Posad.

The posad was the center of trade in Ancient Rus. Merchants and craftsmen resided there and sold goods such as pottery, armor, glass and copperware, icons, and clothing; as well as food, wax, and salt. Most large cities were adjoined by a posad.

As posads developed, they became like villages. And a number of posads even evolved into towns. Those by a monastery were often named after the monastery, Sergiev Posad is named after the nearby Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * T O P * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I actually have to go back, sometime.

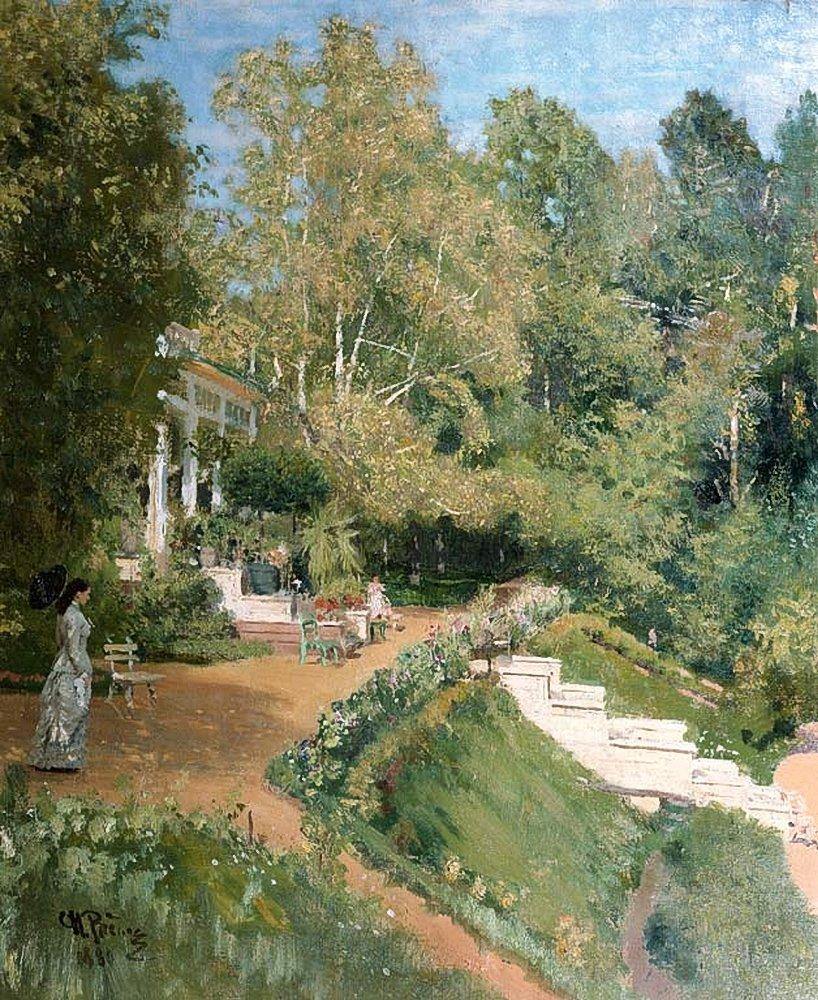

I really would have liked to have visited Abramtsevo, which was situated near Sergiev Posad. It is an estate where many Russian artists lived and worked between 1843 and 1917. I have read a great deal about it and spoke of it in some of my lectures, but have never been there myself. In 2016, when I was in the vicinity, restoration work was in progress; so it did not seem like an appropriate time to visit. I very much regret missing the opportunity of adding my footsteps to those of Michael Vroebel, Vasili Polenov, Viktor Vasnetsov and Valentin Serov.

Left:

Abramtsevo landscape by Ilya Repin, 1880

Right: Abramtsevo landscape by Vasiliy Polenov

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * T O P * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Baba Yaga

Featured in most of the stories is the old crone Baba

Yaga. Once in a while, Baba Yaga is portrayed as kindly, but the norm is

that Baba Yaga is the essence of wickedness. She has iron teeth for

eating children when she can get them (Russian parents tell their

children that Baba Yaga eats only children who misbehave). Her mode of

transportation, the giant mortar that she beats with a pestle to go

faster, is a classic element in Baba Yaga stories. Another motif is her

hut, which as described in the Baba Yaga story presented here, stands on

hen's legs and can move about at whim.

Firebirds and firebrands, forests and fools, water and witches, puissant

princesses and pulchritudinous princes: all of these and more are

elements within the environment of Russian fairy tales. Many of these

factors are similar to those found in fairy tales told all over the

world, as are the history and structure of tales in Russia . However,

the fairy tales of Russia also possess a number of characters who,

though they have counterparts in other cultures, are unique to the

Slavic tradition - including Baba Yaga, Koshchei the Deathless, and

various spirits.

![]()

Once upon a time an old man, a widower, lived alone

in a hut with his daughter Natasha. Very merry the two of them were

together, and they used to smile at each other over a table piled with

bread and jam, and play peek-a-boo, first this side of the samovar, and

then that. Everything went well, until the old man took it into his head

to marry again.

So the little girl gained a stepmother. After that everything changed.

No more bread and jam on the table, no more playing peek-a-boo around

the samovar as the girl sat with her father at tea. It was even worse

than that, because she was never allowed to sit at tea at all anymore.

The stepmother said that little girls shouldn't have tea, much less eat

bread with jam. She would throw the girl a crust of bread and tell her

to get out of the hut and go find someplace to eat it. Then the

stepmother would sit with her husband and tell him that everything that

went wrong was the girl's fault. And the old man believed his new wife.

So poor Natasha would go by herself into the shed in the yard, wet the

dry crust with her tears, and eat it all by herself.

Then she would hear the stepmother yelling at her to come in and wash up

the tea things, and tidy the house, and brush the floor, and clean

everybody's muddy boots.

One day the stepmother decided she could not bear the sight of Natasha

one minute longer. But how could she get rid of her for good? Then she

remembered her sister, the terrible witch Baba Yaga, the bony-legged

one, who lived in the forest. And a wicked plan began to form in her

head.

The very next morning, the old man went off to pay a visit to some

friends of his in the next village. As soon as the old man was out of

sight the wicked stepmother called for Natasha.

"You are to go today to my sister, your dear little aunt, who lives in

the forest," said she, "and ask her for a needle and thread to mend a

shirt."

"But here is a needle and thread," said Natasha, trembling, for she knew

that her aunt was Baba Yaga, the witch, and that any child who came near

her was never seen again. "Hold your tongue," snapped the stepmother,

and she gnashed her teeth, which made a noise like clattering tongs.

"Didn't I tell you that you are to go to your dear little aunt in the

forest to ask for a needle and thread to mend a shirt?"

"Well, then," said Natasha, trembling, "how shall I find her?" She had

heard that Baba Yaga chased her victims through the air in a giant

mortar and pestle, and that she had iron teeth with which she ate

children.

The stepmother took hold of the little girl's nose and pinched it.

"That is your nose," she said. "Can you feel it?"

"Yes," whispered the poor girl.

"You must go along the road into the forest till you come to a fallen

tree," said the stepmother, "then you must turn to your left, and follow

your nose and you will find your auntie. Now off with you, lazy one!"

She shoved a kerchief in the girl's hand, into which she had packed a

few morsels of stale bread and cheese and some scraps of meat. Natasha

looked back. There stood the stepmother at the door with her arms

crossed, glaring at her. So she could do nothing but to go straight on.

She walked along the road through the forest till she came to the fallen

tree. Then she turned to the left. Her nose was still hurting where the

stepmother had pinched it, so she knew she had to go on straight ahead.

Finally she came to the hut of Baba Yaga, the bony-legged one, the

witch. Around the hut was a high fence. When she pushed the gates open

they squeaked miserably, as if it hurt them to move. Natasha noticed a

rusty oil can on the ground.

"How lucky," she said, noticing that there was some oil left in the can.

And she poured the remaining drops of oil into the hinges of the gates.

Inside the gates was Baba Yaga's hut. It wasn't like any other hut she

had ever seen, for it stood on giant hen's legs and walked about the

yard. As Natasha approached, the house turned around to face her and it

seemed that its front windows were eyes and its front door a mouth. A

servant of Baba Yaga's was standing in the yard. She was crying bitterly

because of the tasks Baba Yaga had set her to do, and was wiping her

eyes on her petticoat.

"How lucky," said Natasha, "that I have a handkerchief." She untied her

kerchief, shook it clean, and carefully put the morsels of food in her

pockets. She gave the handkerchief to Baba Yaga's servant, who wiped her

eyes on it and smiled through her tears.

By the hut was a huge dog, very thin, gnawing an old bone.

"How lucky," said the little girl, "that I have some bread and meat."

Reaching into her pocket for her scraps of bread and meat, Natasha said

to the dog, "I'm afraid it's rather stale, but it's better than nothing,

I'm sure." And the dog gobbled it up at once and licked his lips.

Natasha reached the door to the hut. Trembling, she tapped on the door.

"Come in," squeaked the wicked voice of Baba Yaga.

The little girl stepped in. There sat Baba Yaga, the bony-legged one,

the witch, sitting weaving at a loom. In a corner of the hut was a thin

black cat watching a mouse-hole. "Good day to you, auntie," said

Natasha, trying to sound not at all afraid.

"Good day to you, niece," said Baba Yaga.

"My stepmother has sent me to you to ask for a needle and thread to mend

a shirt."

"Has she now?" smiled Baba Yaga, flashing her iron teeth, for she knew

how much her sister hated her stepdaughter. "You sit down here at the

loom, and go on with my weaving, while I go and fetch you the needle and

thread."

The little girl sat down at the loom and began to weave.

Baba Yaga whispered to her servant, "Listen to me! Make the bath very

hot and scrub my niece. Scrub her clean. I'll make a dainty meal of her,

I will."

The servant came in for the jug to gather the bathwater. Natasha said,

"I beg you, please be not too quick in making the fire, and please carry

the water for the bath in a sieve with holes, so that the water will run

through." The servant said nothing. But indeed, she took a very long

time about getting the bath ready.

Baba Yaga came to the window and said in her sweetest voice, "Are you

weaving, little niece? Are you weaving, my pretty?"

"I am weaving, auntie," said Natasha.

When Baba Yaga went away from the window, the little girl spoke to the

thin black cat who was watching the mouse hole.

"What are you doing?"

"Watching for a mouse," said the thin black cat. "I haven't had any

dinner in three days."

"How lucky," said Natasha, "that I have some cheese left!" And she gave

her cheese to the thin black cat, who gobbled it up. Said the cat,

"Little girl, do you want to get out of here?"

"Oh, Catkin dear," said Natasha, "how I want to get out of here! For I

fear that Baba Yaga will try to eat me with her iron teeth."

"That is exactly what she intends to do," said the cat. "But I know how

to help you."

Just then Baba Yaga came to the window.

"Are you weaving, little niece?" she asked. "Are you weaving, my

pretty?"

"I am weaving, auntie," said Natasha, working away, while the loom went

clickety clack, clickety clack.

Baba Yaga went out again.

Whispered the thin black cat to Natasha: "There is a comb on the stool

and there is a towel brought for your bath. You must take them both, and

run for it while Baba Yaga is still in the bath-house. Baba Yaga will

chase after you. When she does, you must throw the towel behind you, and

it will turn into a big, wide river. It will take her a little time to

get over that. When she gets over the river, you must throw the comb

behind you. The comb will sprout up into such a forest that she will

never get through it at all."

"But she'll hear the loom stop," said Natasha, "and she'll know I have

gone."

"Don't worry, I'll take care of that," said the thin black cat.

The cat took Natasha's place at the loom.

Clickety clack, clickety clack; the loom never stopped for a moment.

Natasha looked to see that Baba Yaga was still in the bath-house, and

then she jumped out of the hut.

The big dog leapt up to tear her to pieces. Just as he was going to

spring on her he saw who she was.

"Why, this is the little girl who gave me the bread and meat," said the

dog. "A good journey to you, little girl," and he lay down with his head

between his paws. She petted his head and scratched his ears.

When she came to the gates they opened quietly, quietly, without making

any noise at all, because of the oil she had poured into their hinges

before. Then -- how she did run! Meanwhile the thin black cat sat at the

loom. Clickety clack, clickety clack, sang the loom; but you never saw

such a tangle of yarn as the tangle made by that thin black cat.

Presently Baba Yaga came to the window. "Are you weaving, little niece?"

she asked in a high-pitched voice. "Are you weaving, my pretty?" "I am

weaving, auntie," said the thin black cat, tangling and tangling the

yarn, while the loom went clickety clack, clickety clack. |

"That's not the voice of my little dinner," said Baba Yaga, and she

jumped into the hut, gnashing her iron teeth. There at the loom was no

little girl, but only the thin black cat, tangling and tangling the

threads!

"Grrr!" said Baba Yaga, and she jumped at the cat. "Why didn't you

scratch the little girl's eyes out?" The cat curled up its tail and

arched its back. "In all the years that I have served you, you have

given me only water and made me hunt for my dinner. The girl gave me

real cheese."

Baba Yaga was enraged. She grabbed the cat and shook her. Turning to the

servant girl and gripping her by her collar, she croaked, "Why did you

take so long to prepare the bath?" "Ah!" trembled the servant, "in all

the years that I've served you, you have never so much as given me even

a rag, but the girl gave me a pretty kerchief."

Baba Yaga cursed her and dashed out into the yard.

Seeing the gates wide open, she shrieked, "Gates! Why didn't you squeak

when she opened you?" "Ah!" said the gates, "in all the years that we've

served you, you never so much as sprinkled a drop of oil on us, and we

could hardly stand the sound of our own creaking. But the girl oiled us

and we can now swing back and forth without a sound."

Baba Yaga slammed the gates closed. Spinning around, she pointed her

long finger at the dog. "You!" she hollered, "why didn't you tear her to

pieces when she ran out of the house?"

"Ah!" said the dog, "in all the years that I've served you, you never

threw me anything but an old bone crusts, but the girl gave me real meat

and bread."

Baba Yaga rushed about the yard, cursing and hitting them all, while

screaming at the top of her voice.

Then she jumped into her giant mortar. Beating the mortar with a giant

pestle to make it go faster, she flew into the air and quickly closed in

on the fleeing Natasha.

For there, on the ground far ahead, she soon spied the girl running

through the trees, stumbling, and fearfully looking over her shoulder.

"You'll never escape me!" Baba Yaga laughed a terrible laugh and steered

her flying mortar straight downward toward the girl.

Natasha was running faster than she had ever run before. Soon she could

hear Baba Yaga's mortar bumping on the ground behind her. Desperately,

she remembered the thin black cat's words and threw the towel behind her

on the ground. The towel grew bigger and bigger, and wetter and wetter,

and soon a deep, broad river stood between the little girl and Baba Yaga.

Natasha turned and ran on. Oh, how she ran! When Baba Yaga reached the

edge of the river, she screamed louder than ever and threw her pestle on

the ground, as she knew she couldn't fly over an enchanted river. In a

rage, she flew back to her hut on hen's legs. There she gathered all her

cows and drove them to the river. "Drink, drink!" she screamed at them,

and the cows drank up all the river to the last drop. Then Baba Yaga

hopped into her giant mortar and flew over the dry bed of the river to

pursue her prey.

Natasha had run on quite a distance ahead, and in fact, she thought she

might, at last, be free of the terrible Baba Yaga. But her heart froze

in terror when she saw the dark figure in the sky speeding toward her

again.

"This is the end for me!" she despaired. Then she suddenly remembered

what the cat had said about the comb.

Natasha threw the comb behind her, and the comb grew bigger and bigger,

and its teeth sprouted up into a thick forest, so thick that not even

Baba Yaga could force her way through. And Baba Yaga the witch, the

bony-legged one, gnashing her teeth and screaming with rage and

disappointment, finally turned round and drove away back to her little

hut on hen's legs.

The tired, tired, girl finally arrived back home. She was afraid to go

inside and see her mean stepmother, so instead she waited outside in the

shed. When she saw her father pass by she ran out to him.

"Where have you been?" cried her father. "And why is your face so red?"

The stepmother turned yellow when she saw the girl, and her eyes glowed,

and her teeth ground together until they broke. But Natasha was not

afraid, and she went to her father and climbed on his knee and told him

everything just as it had happened. When the old man learned that the

stepmother had sent his daughter to be eaten by Baba Yaga, the witch, he

was so angry that he drove her out of the hut and never let her return.

From then on, he took good care of his daughter himself and never again

let a stranger come between them. Over a table piled high with bread and

jam, father and daughter would again play peek-a-boo back and forth from

behind the samovar, and the two of them lived happily ever after.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * T O P * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Walking around the Lavra of Sergiev Posad leaves a

very strong impression.

This is The Assumption Cathedral. This cathedral, built in 1559-1585 by order of Ivan

the Terrible, is much larger than the cathedral of the same name in the

Kremlin of Moscow.

Near the north-western corner of the Assumption

Cathedral is the burial-vault of Tsar Boris Godunov and his family.

For those

who are not familiar with him, Boris Godunov was the most powerful man in Russia at

the end of the 16th century, and tsar from 1598 to 1605.

Andrei Rublev's famous icon ‘The Trinity’ is the

central piece

of the iconostasis of the Trinity Cathedral.

The Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius in Sergiev Posad is

the most important Russian monastery and the spiritual centre of the

Russian Orthodox Church.

If you look at the imposing architectural ensemble of the monastery

today, it is difficult to imagine that this impressive complex has grown

out of a group of timbered chapels around the small, wooden Trinity

Church.

The life of Saint Sergius and the monks was in accordance with the laws

of asceticism; everyone took care of a small garden, which had to

provide everything necessary for life...

Nicholas Roerich, 'St Sergius the Builder' 1940

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * T O P * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Sergiev Posad – Moscow (by train)

We were told that very few trains would run on this

route, but that wasn’t exactly the case. There were enough trains, if

one was willing to travel with the local peasants. Those trains had wooden

benches and leaking windows, that didn’t prevent rain and water from

getting in. Puddles on the floors were a common occurrence.

On our trip a woman carrying an overnight bag entered

our compartment. She opened her bag and showed us some pairs of nice and

warm socks. The woman ahead of us showed interest. After a brief

examination of the socks an agreement was reached and the socks were

purchased.

At the next station, our socks saleswoman left the

train.

She was not the only one, however; this encounter was

not the only instance of ‘train sales’.

During our trip we observed purchases of all kinds of

'useful' objects. Saleswomen continually walked the train corridors

loudly promoting such items as scythes, socks, embroidery and

tablecloths, brushes and key rings, and other common items.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * T O

P * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

MOROZKO

Once there lived an old widower and his daughter. In

due time, the man remarried to an older woman who had a daughter herself

from a previous marriage. The woman doted on her own daughter, praising

her at every opportunity, but she despised her stepdaughter.

She found fault with everything the girl did and made her work long and

hard all day long.

One day the old woman made up her mind to get rid of the stepdaughter

once and for all. She ordered her husband: "Take her somewhere so that

my eyes no longer have to see her, so that my ears no longer have to

hear her. And don't take her to some relative's house. Take her into the

biting cold of the forest and leave her there."

The old man grieved and wept, but he knew that he could do nothing else;

his wife always had her way. So he took the girl into the forest and

left her there. He turned back quickly so that he wouldn't have to see

his girl freeze.

Oh, the poor thing, sitting there in the snow, with her body shivering

and her teeth chattering! Then Morozko (the Father Frost), leaping from

tree to tree, came upon her. "Are you warm, my lass?" he asked.

"Welcome, my dear Morozko. Yes, I am quite warm," she said, even though

she was cold through and through.

At first, Morozko had wanted to freeze the life out of her with his icy

grip. But he admired the young girl's stoicism and showed mercy. He gave

her a warm fur coat and downy quilts before he left. In a short while,

Morozko returned to check on the girl.

"Are you warm, my lass?" he asked.

"Welcome again, my dear Morozko. Yes, I am very warm," she said.

And indeed she was warmer. So this time Morozko brought a large box for

her to sit on. A little later, Morozko returned once more to ask how she

was doing. She was doing quite well now, and this time Morozko gave her

silver and gold jewelry to wear, with enough extra jewels to fill the

box on which she was sitting!

Meanwhile, back at her father's hut, the old woman told her husband to

go back into the forest to bring back the body of his daughter. He did

as he was ordered. He arrived at the spot where had left her, and was

overjoyed when he saw his daughter alive, wrapped in a sable coat and

adorned with silver and gold. When he arrived home with his daughter and

the box of jewels, his wife looked on in amazement.

"Harness the horse, you old goat, and take my own daughter to that same

spot in the forest and leave her there," she said.

"Harness the horse, you old goat, and take my own daughter to that same

spot in the forest and leave her there," she said.

The old man did as he was told. Like the other girl at first, the old

woman's daughter began to shake and shiver. In a short while, Morozko

came by and asked her how she was doing.

"Are you blind?" she replied. "Can't you see that my hands and feet are

quite numb? Curse you, you miserable old man!"

Dawn had hardly broken the next day when, back at the old man's hut, the

old woman woke her husband and told him to bring back her daughter,

adding: "Be careful with the box of jewels." The old man obeyed and went

to fetch the girl.

A short while later, the gate to the yard creaked. The old woman went

outside and saw her husband standing next to the sleigh. She rushed

forward and pulled aside the sleigh's cover. To her horror, she saw the

body of her daughter, frozen by an angry Morozko. She began to scream

and berate her husband, but it was all in vein.

Later, the old man's daughter married a neighbor, had children, and

lived happily. Her father would visit his grandchildren every now and

then, and remind them always to respect Old Man Winter.

Father Frost and the step daughter,

Ivan Bilibin, 1932

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * T O

P * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Once

upon a time there lived a woodcutter and his old wife. They were poor

and had no children. The old man cut logs in the forest and carried them

into town; in this way he eked out a living. As they grew older they

became sadder and sadder at being childless. "We are growing so old. Who

will take care of us?" the wife would ask from time to time. "Do not

worry, old woman. God will not abandon us. He will come to our aid in

time," answered the old man.

One day, in the dead of winter, he went into the forest to chop wood and

his wife came along to help him. The cold was intense and they were

nearly frozen. "We have no child," said the woodcutter to his wife.

"Shall we make a little snow girl to amuse us?" They began to roll

snowballs together, and in a short while they had made a "snegurochka,"

a snow maiden, so beautiful that no pen could describe her. The old man

and the old woman gazed at her and grew even sadder. "If only the good

Lord had sent us a little girl to share our old age!" said the old

woman.

They thought on this so strongly that suddenly a miracle happened. They

looked at their snow maiden, and were amazed at what they saw. The eyes

of the snow maiden twinkled; a diadem studded with precious stones

sparkled like fire on her head; a cape of brocade covered her shoulders;

embroidered boots appeared on her feet. The old couple looked at her and

did not believe their eyes. Then the mist of breath parted the red lips

of Snegurochka; she trembled, looked around, and took a step forward.

The old couple stood there, stupefied; they thought they were dreaming.

Snegurochka came toward them and said: "Good day, kind folk, do not be

frightened! I will be a good daughter to you, the joy of your old age. I

will honor you as father and mother."

"My darling daughter, let it be as you desire," answered the old man.

"Come home with us, our longed-for little girl!" They took her by her

white hands and led her from the forest. As they went, the pine trees

swayed goodbye, saying their farewell to Snegurochka, with their

rustling wishing her safe journey, happy life.

The old couple brought Snegurochka home to their wooden hut, their 'isba,'

and she began her life with them, helping them to do the chores. She was

always most respectful, she never contradicted them, and they could not

praise her enough, nor tire of gazing at her, she was so kind and so

beautiful. Snegurochka, nevertheless, worried her adopted parents. She

was not at all talkative and her little face was always pale, so pale.

She did not seem to have a drop of blood, yet her eyes shone like little

stars. And her smile! When she smiled she lighted up the isba like a

gift of rubles.

They lived together thus for one month, two months; time passed. The old

couple could not rejoice enough in their little daughter, gift of God.

One day the old woman said to Snegurochka: "My darling daughter, why are

you so shy? You see no friends, you always stay with us, old people;

that must be tiresome for you. Why do you not go out and play with your

friends, show yourself and see people? You should not spend all your

time with us, aged folk." "I have no wish to go out, dear Mother,"

answered Snegurochka. "I am happy here."

Carnival time arrived. The streets were alive with strollers, with

singing from early morning until late at night. Snegurochka watched the

merrymaking through the little frozen window panes. She watched ... and

finally she could resist no longer; she gave in to the old woman, put on

her little cape, and went into the street to join the throng.

In the same village there lived a maiden called Kupava. She was a true

beauty, with hair as black as a raven's wing, skin like blood and milk,

and arching brows.

One day a rich merchant came through town. His name was Mizgir, and he

was young and tall. He saw Kupava and she pleased him. Kupava was not at

all shy; she was saucy and never turned down an invitation to stroll.

Mizgir stopped in the village, called to all the young girls, gave them

nuts and spiced bread, and danced with Kupava. From that moment he never

left town, and, it must be said, he soon became Kupava's lover. There

was Kupava, the belle of the town, parading around in velvets and silks,

serving sweet wines to the youths and the maidens and living the joyful

life.

The day Snegurochka first strolled in the street, she met Kupava, who

introduced all her friends. From then on Snegurochka came out more often

and looked at the young people. A young boy, a shepherd, pleased her. He

was named Lel. Snegurochka pleased him too, and they became inseparable.

Whenever the young girls came out to stroll and to sing, Lel would run

to Snegurochka's isba, tap on the window and say: "Snegurochka, dearest,

come out and join the dancing." Once she appeared, he never left her

side.

One day Mizgir came to the village as the maidens were dancing in the

street. He joined in with Kupava and made them all laugh. He noticed

Snegurochka and she pleased him; she was so pale and so pretty! From

then on Kupava seemed too dark and too heavy. Soon he found her

unpleasant. Quarrels and scenes broke out between them and Mizgir

stopped seeing her. Kupava was desolate, but what could she do? One

cannot please by force nor revive the past! She noticed that Mizgir

often returned to the village and went to the house of Snegurochka's old

parents. The rumor flew that Mizgir had asked for Snegurochka's hand in

marriage. When Kupava learned this, her heart trembled. She ran to

Snegurochka's isba, reproached her, insulted her, called her a viper, a

traitor, made such a scene that they had to force her to leave.

"I will go to the Tsar!" she cried. "I will not suffer this dishonor.

There is no law that allows a man to compromise a maiden, then throw her

aside like a useless rag!"

So Kupava went to the Tsar to beg for his help against Snegurochka, who

she insisted had stolen her lover.

Tsar Berendei ruled this kingdom; he was a good and gracious Tsar who

loved truth and watched over all his subjects. He listened to Kupava and

ordered Snegurochka brought before him. The Tsar's envoys arrived at the

village with a proclamation ordering Snegurochka to appear before their

master.

"Good subjects of the Tsar! Listen well and tell us where the maiden

Snegurochka lives. The Tsar summons her! Let her make ready in haste! If

she does not come of her will we will take her by force!"

The old woodcutters were filled with fear. But the Tsar's word was law.

They helped Snegurochka to make ready and decided to accompany her, to

present her to the Tsar.

Tsar Berendei lived in a splendid palace with walls of massive oak and

wrought-iron doors; a large stairway led to great halls where Bukhara

carpets covered the floors and guardsmen stood in scarlet kaftans with

shining axes. All the vast courtyard was filled with people.

Once inside the sumptuous palace, the old couple and Snegurochka stood

amazed. The ceilings and arches were covered with paintings, the

precious plate was lined up on shelves, along the walls ran benches

covered with carpets and brocades, and on these benches were seated the

boyars wearing tall hats of bear fur trimmed with gold. Musicians played

intricate music on their tympanums. At the far end of the hall, Tsar

Berendei himself sat erect on his gilded and sculptured throne. Around

him stood bodyguards in kaftans white as snow, holding silver axes. Tsar

Berendei's long white beard fell to his belt. His fur hat was the

tallest; his kaftan of precious brocade was embroidered all over with

jewels and with gold. Snegurochka was frightened; she did not dare to

take a step nor to raise her eyes. Tsar Berendei said to her: "Come

here, young maiden, come closer, gentle Snegurochka. Do not be afraid,

answer my questions. Did you commit the sin of separating two lovers,

after stealing the heart of Kupava's beloved? Did you flirt with him and

do you intend to marry him? Make sure that you tell me the truth!"

Snegurochka approached the Tsar, curtsied low, knelt before him, and

spoke the truth; that she was not at fault, neither in body nor in soul;

that it was true that the merchant Mizgir had asked for her in marriage,

but that he did not please her and she had refused his hand. Tsar

Benendei took Snegurochka's hands to help her to rise, looked into her

eyes and said: "I see in your eyes, lovely maiden, that you speak the

truth, that you are nowhere at fault. Go home now in peace and do not be

upset!" And the Tsar let Snegurochka leave with her adoptive parents.

When Kupava learned of the Tsar's decision she went wild with grief. She

ripped her sarafan, tore her pearl necklace from her white neck, ran

from her isba, and threw herself in the well.

From that day on, Segurochka grew sadder and sadder. She no longer went

out in the street to stroll, not even when Lel begged her to come.

Meanwhile, spring had returned. The glorious sun rose higher and higher,

the snow melted, the tender grass sprouted, the bushes turned green, the

birds sang and made their nests. But the more the sun shone, the paler

and sadder Snegurochka grew.

One beautiful spring morning Lel came to Snegurochka's little window and

pleaded with her to come out with him, just once, for just a moment. For

a long while Snegurochka refused to listen, but finally her heart could

no longer resist Lel's pleas, and she went with her beloved to the edge

of the village.

"Lel, oh my Lel, play your flute for me alone!" she asked. She stood

before Lel, barely alive, her feet tingling, not a drop of blood in her

pale face! Lel took out his flute and began to play Snegurochka's

favorite air. She listened to the song, and tears rolled down from her

eyes. Then her feet melted beneath her; she fell onto the damp earth and

suddenly vanished. Lel saw nothing but a light mist rising from where

she had fallen. The vapor rose, rose, and disappeared slowly in the blue

sky ...

Yevgenia Zbrueva as Lel in the opera The Snow Maiden, 1894.

It's an opera of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, composed during 1880-1881

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * T O P * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(to be continued....)