Cedar Gallery

Home

|

Cedar info |

News |

Contact |

![]() Dutch

Dutch

PAINTERS

PAINTING is a mode of expression and the forms are numerous. Drawing, composition or abstraction and other aesthetics may serve to manifest the expressive and conceptual intention of the practitioner. Paintings can be naturalistic and representational (as in a still life or landscape painting), photographic, abstract, be loaded with narrative content, symbolism, emotion or be political in nature.

A portion of the history of painting in both Eastern and Western art is dominated by spiritual motifs and ideas; examples of this kind of painting range from artwork depicting mythological figures on pottery to Biblical scenes rendered on the interior walls and ceiling of The Sistine Chapel, to scenes from the life of Buddha or other scenes of eastern religious origin.

WHO are the persons, who make these paintings? And

what does this specific painter create?

Everyone has heard of Van Gogh, Rembrandt or Picasso. Sometimes

artists become famous for their unique style.

We do also appreciate thier works for other reasons, however.

So let’s enjoy (the works of) the artists I selected here. And let’s

have a close look at some details.

Aly Wagenvoorde, 2018

Most pictures are taken at exhibitions, by me and my husband, ©PAM PHOTOS Delden

(More painters will be added, over the years...)

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Marlene Dumas - Gustav Kimt - Robert Mangold - Christian Schad - Matthias Weischer -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

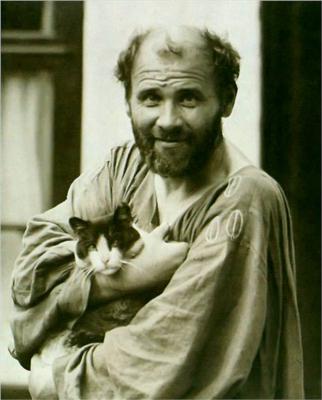

Gustav Klimt (1862 - 1918)

In Austria, the revival of industry at the end of the 19th century had produced a new class of wealthy capitalists. Many members of this new class imitated the lifestyle of the nobility and became enthusiastic art collectors. One of the consequences of this was the emergence of the Wiener Secession, an artists' association that was founded in 1897. The most prominent painter is Gustav Klimt.

These types of organizations were established as an alternative to the academies, that were too conservative, in the eyes of the artists. In Germany and Austria they were referred to as ‘Secession’. They can be compared to the ‘Salons des indépendants’ in France, which were also trying to show art freely, without being subject to all kinds of rules and regulations. The Secession did not have a clear program, but its goals were ambitious: These artists wanted to renew the entire Austrian art world. They also wanted to bring all visual and applied arts together. What they were searching for was a so called Gesamtkunstwerk.

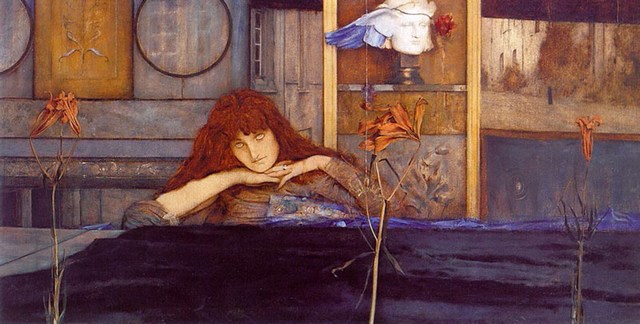

I lock my door upon myself - Fernand

Khnopff

Symbolists from abroad were very popular. Painters like Jan Toorop and

Fernand Khnopff for example. ‘I lock my Door upon myself’ is an

interesting example. Maybe I'll come back to this later. For now it is enough to say that the title clearly reflects what symbolism stands for.

You close the door to the outside world and focus on your inner self.

The purpose of the symbolists was to turn away from what they saw as the

‘materialism of impressionism.’ Instead, they tried to evoke something,

indicate a mood, or an abstract idea - to make their work become ‘more’,

like poetry and music. Neither of them shows the world in a literal way.

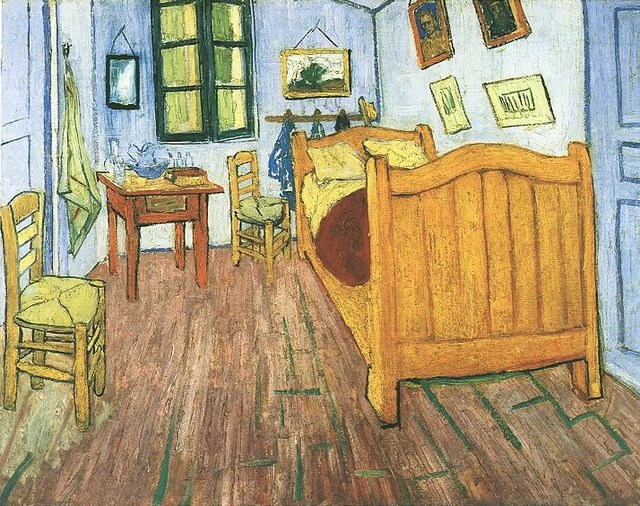

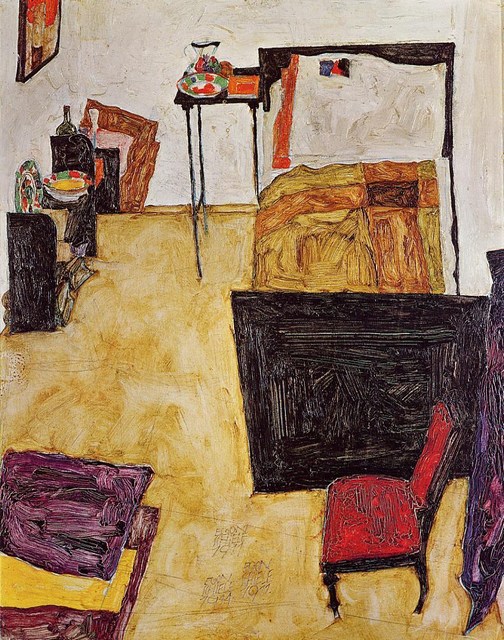

Vincent van Gogh and Edward Munch were also popular by the Secession.

Left: Van Gogh

Right: Schiele

Gustav Klimt

Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) studied at the Viennese Kunstgewerbeschule.

From 1882 he and his brother Ernst made murals for public buildings,

works that became more and more experimental. His erotic ornaments and

paintings for Viennese university caused a scandal in 1894.

In 1897, in opposition to the classicist Viennese establishment, he

founded Secession, along with other artists, to stimulate the work of

young avant-garde artists. Among the members of the Vienna Secession

were not only painters, but also architects and decorative artists. They

published their own magazine, in which they set out their ideas.

Their motto was: "Let every era have its art, let art have its freedom."

This group of artists developed the Viennese version of Art Nouveau and

was strongly focused on developments in international Western art. But

despite that, the greatest importance of the movement was in Klimt's

work.

In 1891, Klimt met Emilie Flögel, who became his partner and muse.

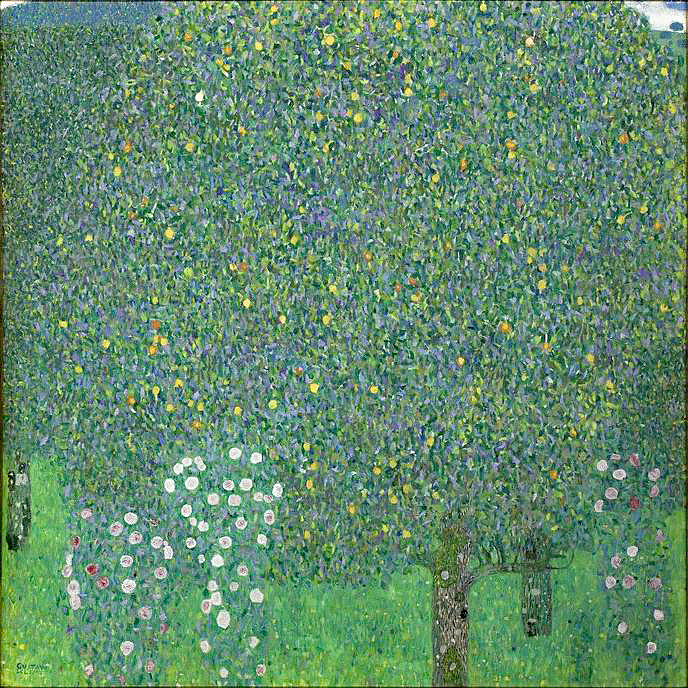

Every summer he went on holiday in Salzkammergut, with her and her family. And that resulted in many paintings of landscapes, including ‘Rose bushes under the trees’, around 1905. The flat space and wavy contours show that he was influenced by Japanese art. Yet the work also looks almost abstract.

If we look at Sunflower (1906-1907), it is a more naturalistic painting. It is interesting to compare this downturned sunflower with The Kiss, which follows after 'Philosophy' (at this section).

Philosophy

A storm of criticism broke out when Klimt exhibited his Philosophy and

Medicine (ca. 1900). The pronounced erotic nature of the two paintings

in particular caused a stir.

German modernists were strongly interested in what was happening in

other countries at that time. The Austrians mainly reflected on older

examples of Symbolism and the Jugendstil. Klimt liked to use allegories

(= symbolic representations) and had a lot of influence on Schiele.

After a series of disagreements, Klimt left the Vienna Secession in 1905 and set up a new group, the Klimtgruppe.

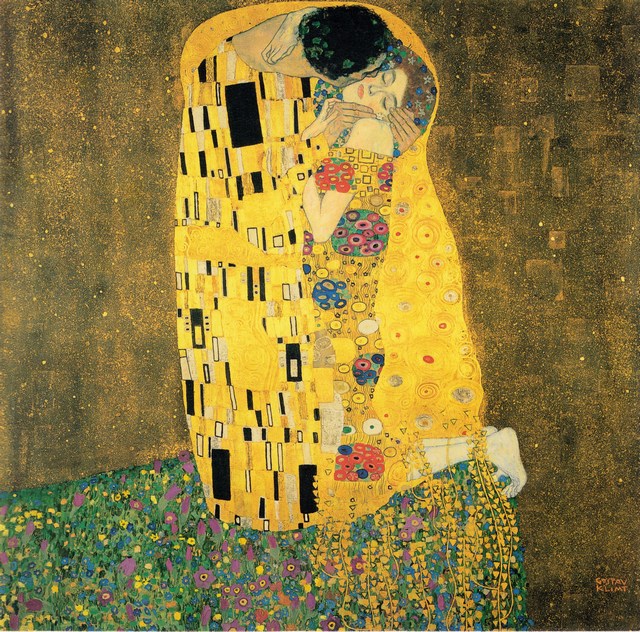

The Kiss was exhibited in 1908 for the first time. It is the most famous painting by Gustav Klimt. This painting is part of a series of paintings that he has devoted to the theme of ‘Embrace.’

The Kiss is the highlight of Klimt's ‘Golden Phase’(ca.1899-1910). If we

take a closer look at the painting, we see at the feet of the woman that

she is kneeling. Even though the man keeps his head bowed, it is likely

that the woman is (much) taller than the man.

The woman seems to kneel in a bed of flowers, although the perspective

is distorted. On her side, golden 'ribbons with triangular ornaments'

fall over the flowers. It could be that it ís meant to represent the

extremely long hair of the woman. This makes her look like a ‘femme

fatale’. An archetype that appears in both art and literature and is

presented as a woman who uses her beauty and sexuality to seduce men. A

femme fatale is arrogant, strong, sexually independent, intelligent and

has a low image of men. Femmes fatales are often portrayed with

extremely long hair. They could use this to entangle or tie men.

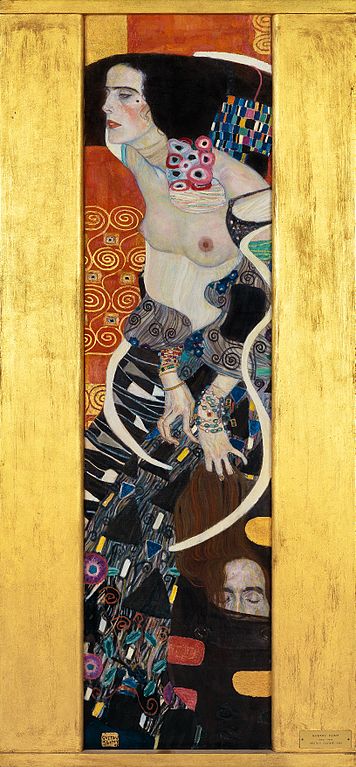

Above, left: Judith I, 1901 - The Association of Death and Sexuality, by Eros and Thanatos, fascinated Freud and Klimt. And in fact all of Europe, in those days.

Above, right: Judith II (Salomé), 1909 - Judith or Salomé? The Bible story about Judith is one of the few in the Bible where the woman is more powerful than the man. Judith chops off Holofernes' head. Many artists have been inspired by this dramatic story. Salome caused the beheading of John the Baptist. She too was an example of a femme fatale.

The painting ‘Adèle Bloch-Bauer I’ is another top piece from the same period. It is a work of 138 x 138 cm. Klimt worked on it for at least three years, between 1904 and 1907. He made hundreds of sketches and incorporated real gold into it.

For sixty years this painting was the signboard of a Galerie in Vienna. However, the painting fell under the ‘Nazi robbery art’ because it was stolen from the Jewish owners. After years of legal struggle, the Austrian government had to return the artwork to the rightful heirs.

The heirs of the Bloch-Bauer family, including Maria Altman, then sold

the painting, in June 2006. The price at that time was the highest

amount anyone had ever paid for a painting.

In November 2006, a so-called dripping from Jackson Pollock was sold for

an even higher amount.

Death and Life, (right: detail)

During the last years of his life, Klimt focused on women's portraits.

Those who embrace Klimt's work usually do this because of their

fascination with Klimt's main theme: (the beauty of) women.

In addition, he mainly painted landscapes and erotic allegories. One of

those later works is 'Death and Life.’ He started this work in 1908, the

year of the Kunstschau in Vienna, which he had co-organized. He did not

finish the painting until 1915. It is a work of his Golden Phase too. It

is a large painting, 178 x 198 cm. It is now in the Leopold Museum in

Vienna.

The themes of Women, Life and Death were central to his time and were also embraced by painters such as Oskar Kokoschka, Edvard Munch and Egon Schiele.

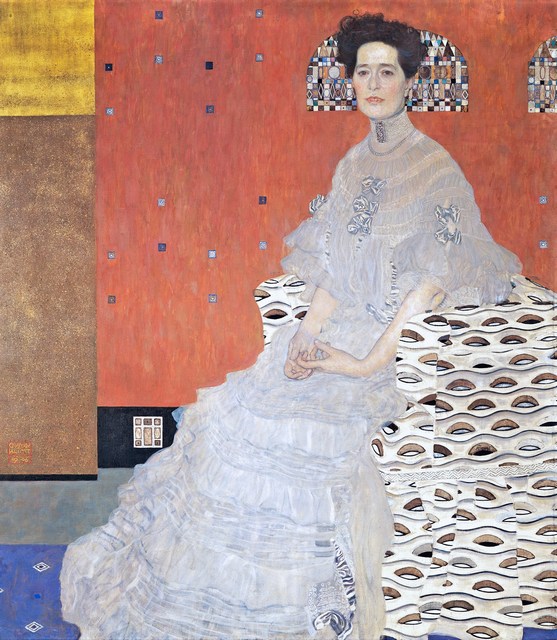

Left: Portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl 1917/1918 - in Belvedere, Vienna,

right: Portrait of Fritza Riedler, 1906

The three stages of life of women, 1905

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - T O P - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

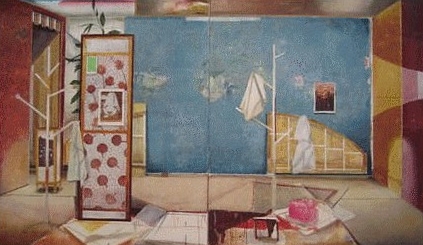

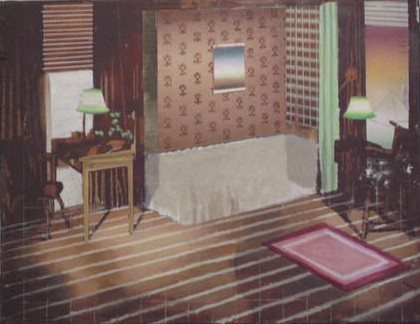

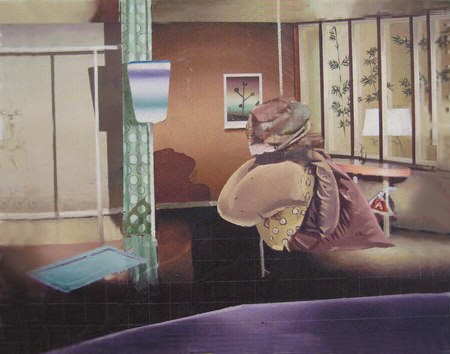

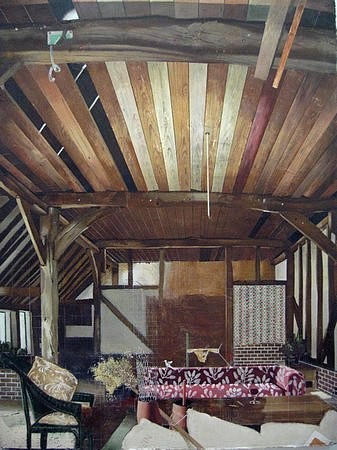

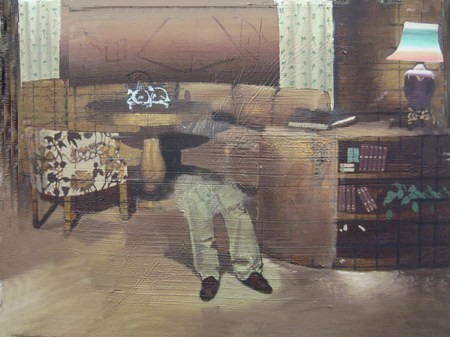

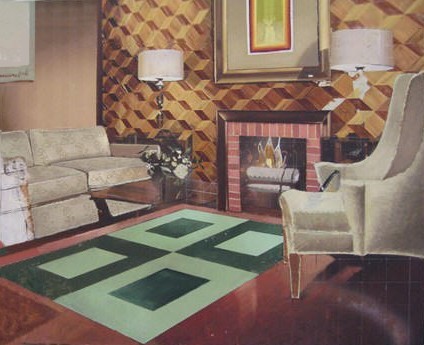

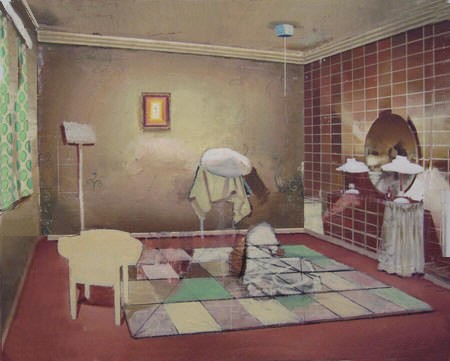

In 2008 we visited the exhibition of interiors, painted by Matthias Weischer, in the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague. Matthias Weischer (1973, Elte, Westphalia) came to prominence in the late '90s as a member of the Neue Leipziger Schule. Weischer spent some time at the Villa Massimo in Rome.

Matthias Weischer studied from 1995 to the end of

2003 at the Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst in the Eastern German

city of Leipzig, where he was influenced by Neo Rauch and met artists

like David Schnell. Here some likeminded artists formed the group known

as the Neue Leipziger Schule. Artists regarded as members of this group

are conspicuous chiefly for the theatrical nature and large size of

their canvases.

Weischer's paintings are typically depictions of worn interiors that remind us of times gone by. He composes these inviting interiors like theatre sets, using a variety of objects in an unconventional way. It has an alienating effect on us. If you see these paintings, you will probably become aware of Weischer's fascination with colour, form, composition and structure.

Are these real rooms or do they just exist in the

imagination of Matthias Weischer?

Weischer draws inspiration for these canvases from illustrations in

books of cultural history or interior design magazines of the 1950s and

’60s.

Lounge 2005, Matthias Weischer

Trousers 2005, Matthias Weischer

In 2007, a scholarship enabled Weischer to work for a year at the Villa Massimo in Rome. This has brought about interesting changes in his work. His latest paintings are much smaller and tend to depict almost unfurnished interiors. His palette is now reminiscent of medieval Italian frescos, with colours like pale blue and pink predominating. His compositions have become increasingly free, intuitive and spontaneous. The previous superabundance of objects has been replaced by a single tree trunk, mat or skull. The starting point is no longer magazine photos, but a theatre that Weischer built for himself in his room in order to try out new and ever-changing compositions. In the space of just a couple of years, Weischer’s artistic development has taken an unexpected turn, with the meticulously planned paintings being replaced by more casually organised pictures and the large, complex compositions turning into small, poetic tableaux.

Pipe 2007, Matthias Weischer

Photos: ©PAM PHOTOS Delden

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - T O P - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

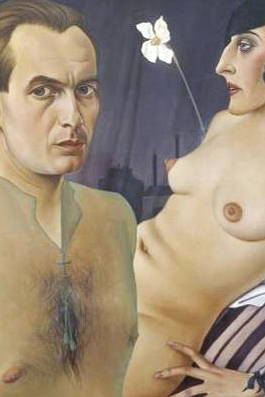

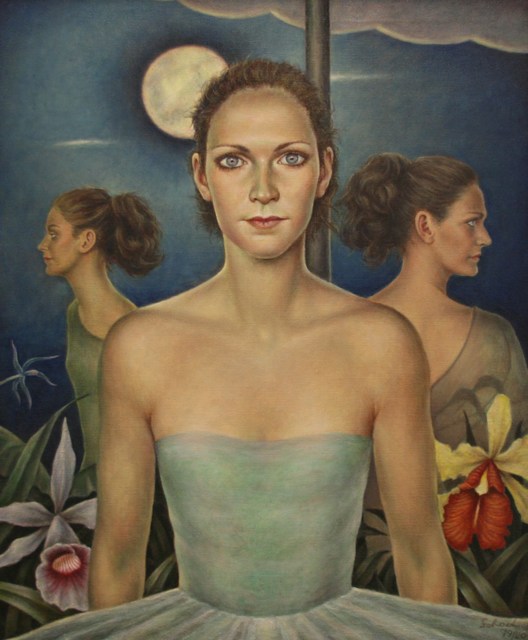

Sonja, 1928

Christian Schad (1894-1982) is best known for his important role in the German Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement. Examples of his work in this field are found in leading collections all over the world. Their coolness, smooth surface, erotic charge and conspicuously large eyes (‘mirrors of the soul’) make his portraits icons of the 1920s. Schad’s ability to capture both the decadence and the underlying malaise of the ‘roaring twenties’ is unequalled. In this exhibition too, the main emphasis is on Schad’s key achievements of the inter-war period. His earlier work, influenced by Cubism and Dadaism, is less well-known but equally lauded. Schad was one of the inventors of the photogram, which the Dadaist Tristan Tzara dubbed the ‘Schadograph’: a photograph made by placing objects on photographic paper and directly exposed to light (without the use of a camera). His photographs were an example to contemporaries like Man Ray, László Maholy-Nagy and El Lissitzky and continue to inspire countless artists even today.

Maika, 1929

After the Nazis seized power in Germany, Schad adopted a low profile and tried to earn a living by drawing conservative, soft-focus portraits. In 1942, one such portrait commission took him to Aschaffenburg in northwest Bavaria, where he was to settle and remain until his death forty years later. The little-known works that he produced there in the 1950s are marked by a tendency towards abstraction. During that period he broke new ground in his printmaking and with his Resopal paintings. In the 1960s and ‘70s het produced what he himself described as Magic Realism: masterly realistic paintings enriched by fantastic and illogical elements. Contemporary with international art movements like Pop Art and Photorealism, these works show how Schad was still keeping pace with new developments well into his seventies. But even in his revisiting of Dadaist techniques and art forms, Schad’s work shows interesting similarities with that of young artists of the period.

For a period after the Second World War, naturalistic

painting was taboo in West Germany - following the country’s experience

of totalitarianism, there was a belief that the art of a democratic

society should necessarily be abstract.

For that reason, Schad was better known during that time in East

Germany, where his work was exhibited as early as 1956. Although he

lived to a great age, he himself derived little benefit from his later

discovery and the growing acclaim for his late as well as earlier work.

The frozen immobility of this double portrait is typical of Schad’s work at this period. The unprecendentedly meticulous depiction of the skin and, more particularly, the cold gaze of the subjects show Schad’s unflinching virtuosity at its best. Despite the strong focus on the eyes, the dominant impression is one of the impassive detachment and absence of emotion. Agosta, a medical curiosity, exhibited his deformities at the Onkel Pelle fairground in the Wedding area of Berlin. Because of his deformed thorax, he was also used for teaching purposes at Berlin’s university hospital, the Charité. Rasha was a negress who presented an act with a boa constrictor.

Self portrait with model, 1927

Schad’s Self-Portrait with Model is among the most renowned paintings of the New Objectivity movement. It is an icon of the pervasive disenchantment of the period. Schad portrays himself not – as perhaps might be expected – as an artist, but as a protagonist in a provocative sex drama. The picture shows him sitting in front of a naked woman, in an apparently post-coital situation, subjecting himself to his own merciless scrutiny. His transparent green shirt acts as a protective carapace and in his fascinated self-absorption he totally ignores the woman behind him. The voile shirt actually intensifies the impression of nakedness, symbolising both sensuality and imperviousness to emotion. The artist’s expression is defensive and the atmosphere frigid. The protagonists have nothing to say to each other. His body is turned to the right, hers to the left, as if deliberately averted from each other.

Between their heads rears a narcissus, perhaps symbolizing the

narcissism of the two protagonists. The woman’s dark hair is arranged in

a page-boy style with a side parting. She represents a type of woman

much in vogue in the 1920s: not particularly attractive but not exactly

ugly. Her left cheek bears a sfregio, a scar of the kind that

jealous men in southern Italy were in the habit of inflicting on their

women. Schad knew of this phenomenon from his time in Naples. The

backdrop is the dark silhouette of a city against a night sky with

factory chimneys.

The absence of perspective gives the scene a dreamlike quality while the

exaggerated stress on individual details, the razor-sharp delineation of

the various elements and the austere linearity of the depiction create

the atmosphere of glassy unreality that is so typical of this phase of

Schad’s career, of which this portrait is the culminating achievement.

Bettina (his last wife), 1977

Post-war works

Schad’s post-war work is relatively little known. The

period begins with a complete change of style compared with the 1940s

and an interest in international developments. Schad’s work is now

clearly influenced by his friendship with Francis Picabia, his

admiration for Jean Cocteau and Pablo Picasso, and his involvement with

an exhibition of work by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. In the GDR, he became

well-known and a number of East German artists regarded his portraits as

exemplary. However, he refused a post at the academy of art in East

Berlin. In the late ‘60s, he produced a series of collages which have to

this day never been published but which show similarities to Pop Art.

His highly simplified woodcuts of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s also find

parallels in American Pop Art and commercial graphics.

Pavonia, 1966

Although he continued to experiment eagerly on paper, the few canvases he produced over the last two decades of his life (at a rate around one or two a year) remain true to the Realist tradition. In the 1960s, he reverted to Magic Realism and the themes of his Berlin period, producing paintings like Engel im Separee (Angel in the Private Room) and Pavonia, which allude symbolically to the sexuality of bohemia. The clarity of these late paintings surpasses even that of his work from the 1920s and makes them, for that very reason, appear excruciatingly slick. Schad’s entirely individual portrait style, his Old Masterly painting technique, the almost trompe l óeil representation of skin and – last but not least – the latent eroticism of his pictures still remain sources of inspiration for artists today.

Werdandi, 1979

We are grateful for the information we got from the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague, Holland

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - T O P - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

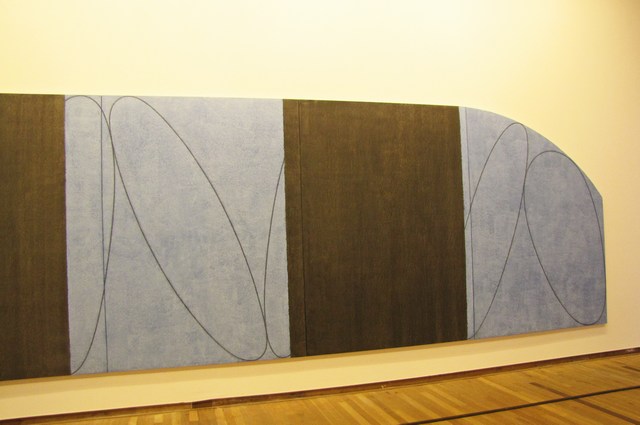

ROBERT MANGOLD

1937 North Tonawanda (NY) – Washingtonville (NY)

The generation to which Mangold belongs is influenced strongly by the Abstract Expressionism of artists such as Barnett Newman.

Barnett Newman (January 29, 1905 – July 4, 1970) was an American artist. He was born in New York City, the son of Jewish immigrants from Poland. He studied philosophy at the City College of New York and worked in his father's business manufacturing clothing. He later made a living as a teacher, writer and critic. From the 1930s he made paintings, said to be in an expressionist style, but eventually destroyed all these works.

Typical of Newman's later work, is the use of pure and vibrant color and

the zip. The zip remained a constant feature of Newman's work throughout

his life. In some paintings of the 1950s, such as The Wild, which is

eight feet tall by one and a half inches wide (2.4 meters by 2

centimeters), the zip is all there is to the work. The zips define the

spatial structure of the painting, while simultaneously dividing and

uniting the composition. Newman also made a few sculptures which are

essentially three-dimensional zips.

Although Newman's paintings appear to be purely abstract, and many of

them were originally untitled, the names he later gave them hinted at

specific subjects being addressed, often with a Jewish theme. Two

paintings from the early 1950s, for example, are called Adam and Eve,

and there is also Abraham (1949), a very dark painting, which as well as

being the name of a biblical patriarch, was also the name of Newman's

father, who had died in 1947.

The outdoor sculpture, "Broken Obelisk" by Barnett

Newman, is permanently installed in the reflecting pool on the grounds

of Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas, USA.

The Stations of the Cross series of black and white paintings (1958–66), begun shortly after Newman had recovered from a heart attack, is usually regarded as the peak of his achievement. The series is subtitled "Lema sabachthani" - "why have you forsaken me" - the last words spoken by Jesus on the cross, according to the New Testament. Newman saw these words as having universal significance in his own time. The series has also been seen as a memorial to the victims of the holocaust. As this is about Robert Mangold, the last thing I mention about Barnett Newman is, that he is seen as one of the major figures in Abstract Expressionism and one of the foremost of the Color Field painters.

As said before, the generation of Mangold is

influenced strongly by Abstract Expressionism. Movements like Minimal

and Conceptual Art arose in reaction to this.

In his work, Mangold has always adhered to the same strict formula of

striving for a balance between surface, colour, line and form. His work

is characterized by his use of the ‘shaped canvas’. The artists,

however, regards his works as paintings rather than objects, even though

he claims not to be interested in painting techniques.

Mangold starts each of his works by drawing quick sketches, in which he

makes the most important decisions intuitively. The best ideas are

developed on a larger scale, in graphite and pastel on paper, after

which several versions are created on canvas.

In pencil on the shaped canvas, he creates a grid structure, which he

uses to draw the thicker lines: ovals, waves, scrolls and circles. The

lines appear mathematical in the precision of their execution, but from

close up you can see that they are drawn by hand, over and over again

until the right thickness has been achieved. The element of line –

linear configurations drawn in pencil – is as important in his work as

colour. To emphasize this, Mangold opted for the visible pencil line

rather than the line drawn in the paint layer, in which the line is part

of the paint and not an autonomous form. In his early works the linear

image was determined only by the dividing line between the panels.

Although colours play an important role, they are inconspicuous and

neutral, and expressly in balance with the shape of the canvas. In order

to restrict the personal touch as far as possible, the paint is usually

applied with a roller in several thin layers.

Although Mangold’s works can be taken in at a glance (something the

artist aims for), they only fully reveal themselves on longer

contemplation.

There is a paradox between what is there and what is not there, and a

role is also played by the remaining space between the panels and the

recesses.

©pictures:

©PAM PHOTOS

Delden &

bonnefantenmuseum

© picture ‘Broken Obelisk’: Ed Uthman, Houston, Texas, USA

We are grateful for the information we got from the Bonnefantenmuseum,

Maastricht and from Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - T O P - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

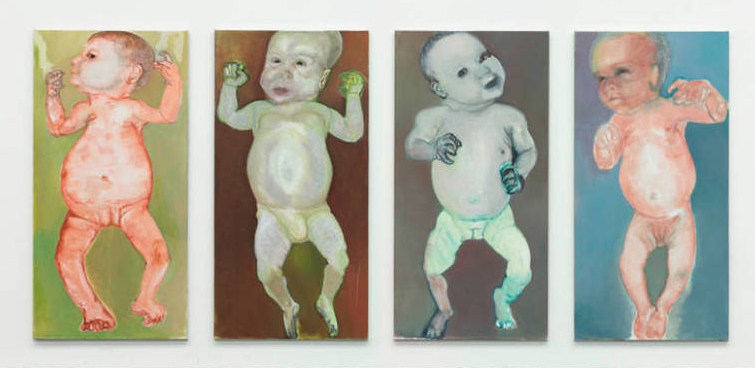

Marlene Dumas (Cape Town, 3. August 1953) is an artist, who was born in South Africa. She has lived and worked in Amsterdam since 1976 and therefore is considered as a Dutch artist.

The work of Marlene Dumas deals with the tension between watching and being watched – and in fact – with the problem of interpretation. She makes frequent use of existing depictions, from pornographic pictures and police photographs to art reproductions, which she collects for her own personal archive of visual material. This material reflects the social codes that determine how we look at things: Dumas enjoys undermining these codes and revealing their inconsistencies. Her uneasiness with the ideal of reducing the artwork to its essence can be explained from this point of view. To her, there is no single essence, no single truth.

For example in The First People from 1990, that exists of four life-size

baby portraits. Four newborn babies have been caught in awkward poses of

uncoordinated helplessness, and blown up to the height of fully-grown

adults. Dumas demonstrates both their vulnerability and the alien nature

of their bulbous bodies and uncontrolled expressions. And look at the

flesh of the babies. These babies are not painted very sentimental, are

they?

The enlarged representation of their bodies are experienced as very

shocking elements. These reactions seem to be influenced by cliché

images of the babies from the commercial world, that seem to be the

present day norm.

‘Certainly no Pampers babies,’ says Dumas. Why is the vulnerable and

greatly enlarged rendering of these baby bodies shocking to many people?

Responses seem to have been unconsciously influenced by the advertising

cliché of the happy baby which has become the norm.

These paintings of Dumas are fairly realistic, precisely by way of

several non-realistic measures, such as the use of scale enlargement and

the technique by which she allows details to flow together or be

accentuated. ‘Motherhood is a shock,’ says Dumas, ‘because you haven’t

realized how the babies actually look.’ Perhaps her ‘first people’

represents some aspect of that confrontation.

Selfportrait at noon, 2008

The Last Supper, 1985-1991

The ritual (with doll), 1992

Pictures: ©PAM PHOTOS Delden

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - T O P - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

So you are a painter too? In that case we invite

you to introduce yourself and send us some pictures of your work.

All submissions will receive serious

consideration.

We look forward to your participation.