In Arabian and Muslim folklore jinns are

ugly and evil demons having supernatural

powers which they can bestow on persons

having powers to call them up. In the

Western world they are called genies. Legend

has it that King Solomon possessed a ring,

probably a diamond, with which he called up

jinns to help his armies in battle. The

concept that this king employed the help of

jinns may have originated from 1 Kings 6:7,

"And the house, when it was in building, was

built of stone made ready before it was

brought there, so there was neither hammer

nor axe nor and tool of iron heard in the

house, while it was in building."

In Islam, jinns are fiery spirits (Qur'an

15:27) particularly associated with the

desert. While they are disruptive of human

life, they are considered worthy of being

saved. A person dying in a state of great

sin may be changed into a jinni in the

period of a barzakh, separation or barrier.

The highest of the jinns is Iblis, formerly

called Azazel, the prince of darkness, or

the Devil. The jinns were thought by some to

be spirits that are lower than angels

because they are made of fire and are not

immortal. They can take on human and animal

shapes to influence men to do good or evil.

They are quick to punish those indebted to

them who do not follow their many rules.

In the "Arabian Nights" jinns or genies came

from Aladdin's Lamp.

There are several myths concerning the home

of the jinns. According to Persian mythology

some of them live in a place called

Jinnistan. Others say jinns live with other

supernatural beings in the Kaf, mystical

emerald mountains surrounding the earth

Cedar Gallery

Home

|

Cedar info |

News |

Contact |

![]() Dutch

Dutch

Engels

Engels

![]()

Berenice

The Djinn Who Lives Between Night and Day

The Field of

the Forty Steps 1687

Dr. Heidegger's Experiment

The Origin of Tis Lake

Violonist hit by Fish 1890

The Djinn Who Lives Between Night and Day

The djinn Al-faq lived in the crack between night and day. He rarely

ventured out into the worlds of his fellow djinn, much less into the

world of mortal men.

No one but God and Al-faq himself knew whether or not he was a faithful

djinn, so the obedient sprits and disobedient alike thought of him as

one of their own.

Djinn of both kinds visited Al-faq to tell him their stories.

Tayab, the djinn of ashes, came to the crack between night and day.

Laughing, he called out, "Cousin! I have such a story to tell you!"

"What have you done now, Tayab?"

The djinn of ashes only laughed some more, so Al-faq said, "Well, come

in, cousin, and have some tea. You must tell me your tale from the

beginning."

When the tea was brewed, Tayab said, "Do you know the people of the red

desert? The ones who live along the river?"

Al-faq gave no answer but nodded for Tayab to continue.

"The plague came to them," said the djinn of ashes. "Every house had its

dead. You never heard such wailing! That was what drew me, cousin. The

anguish of the living. All those lamentations carried on the wind...I

know an opportunity when I hear one!"

Al-faq said, "Go on."

"From one house, I heard shrieks more terrible than all the rest. There

a woman was tearing at her clothes, pulling out her hair. Her husband

tried to hold her hands at her sides. He was crying, too, but not like

her. His face was wet, but he was silent. Her arms and his were bloodied

where she had scratched them. And her keening! Oh, I have seldom heard

grief like hers. It was delicious," Tayab said, "because I was sure I

could make something of it."

"Some mischief," said Al-faq. He sipped his tea.

"Better than mere mischief," said Tayab. "Now, listen. I sniffed around

their house, and in seven places I found the shadow of the dark angel.

Seven times during the plague he had entered and taken a soul. Children,

I guessed. This woman had borne seven children, and now all of them were

dead. When she was too spent to cry out, she whispered their names." He

told Al-faq what the names of the children had been. "Her husband tried

to comfort her. Useless. He said her name, and she would not answer.

When he tried to meet her gaze, she turned away."

"His grief must have been as great."

"Perhaps, perhaps. Who can tell when they aren't loud like her, when

they don't rend their clothes? So I waited until he was asleep. Her eyes

were still wide open, though it was too dark for her to see. I knelt

over her and I whispered, 'Mortal woman, I am the angel of the gate, and

I have heard your prayers.'"

"The angel of the gate?" said Al-faq.

"It's nothing. I made it up. But I said to her, 'I will return your

children to life if you will but keep faith with me.'"

"And if an angel hears of this?"

"But I didn't take the name of any angel, cousin. Didn't I just say that

I made it up? I said to the woman, 'Get up. Go out. Walk west. Go until

you can go no farther. I will give you a sign that your children have

returned, but you must stay there by the sea, alone, with nothing. You

must never speak again. You must never seek your children, for if you

find one then all seven must die.'"

"And she agreed to this bargain?"

"She did! She got up without waking her husband. She took only the

clothes she wore, and she walked! Day and night she walked! Out of the

desert and over the mountains, all the way to the sea!"

"And you? Did you return her children to life?"

Tayab laughed. "Return them to life?" He held his sides and laughed some

more. "Well, I did what I could, cousin. I did all that it was in my

power to do. I came to her in the night and told her to look to the

eastern sky. Stars fell from the heavens, and as each one fell, I gave

it the name of one of her children."

"She believed you."

"Far better than believed me, cousin, and that is the sugar in the tea!

I left her. And when I returned the next night, there she was within

sight of the waves, sheltering in a cave in the cliffs! I said, 'Now,

listen, mortal woman. I am no angel. I am a djinn. As for you, I have

never met a greater fool, for I can no more restore your children to

life that I can make the sun rise in the west. You don't need to stay

here and starve beside the sea. Go home, now. Go home!'"

"And did she?"

"That's the wonder!" The djinn of ashes laughed once more. "She would

not answer me, for I had told her that she must not speak. And she would

not believe me, for I had told her that she must keep faith with the

angel of the gate. So there she stayed, wordless, friendless, with only

a cave for shelter, steady in her faith in a divine servant that does

not exist!"

"But you exist, cousin."

"I do, to be sure," said Tayab with a grin.

"And did she starve?"

"Villagers by the sea found her. They bring her food. They think she is

a holy woman." He laughed again.

"And what of her husband?"

"That's not my story, cousin. He still lives, I suppose, if he has not

died yet."

"I wonder about him."

Tayab waved the thought away. "But what do you think? I took everything

from her, even more than I intended! And now even if I try to return

what I stole, she won't take it! Have you ever heard of thievery such as

mine?"

Al-faq stroked his face with his long fingers and gave no answer.

Perhaps Tayab expected none.

When the djinn of ashes had gone, Al-faq left his home in the crack

between night and day. He went to the world of mortal men. It took him a

long time to find the red desert and even longer to find the house with

seven now fading shadows. The fields next to the house was overgrown.

The man who lived there was hollow-eyed and thin.

Al-faq waited for nightfall. When at last the man fell into his bed, he

moaned his wife's name. Al-faq leaned close in the darkness and said,

"'Mortal man, I am the angel of the gate, and I have heard your prayers.

As you feared, your wife, like your children, is dead. I will return

them all to life if you will but keep faith with me."

"Yes?" said the man. "You can do this?"

"Get up," said Al-faq. "Go out. Walk south. Walk until you can go no

farther. I will give you a sign that your wife and children have

returned to life, but you must stay there by the sea, alone, with

nothing. You must never speak again. You must never seek the ones you

love, for if you find one, then all eight must die."

The man got up. He threw on his clothes. He took up his walking stick

and set out at once. Through the night he walked. He walked through the

next day. In time, he crossed the desert. In time, he crossed the

plains. Al-faq, invisible, came behind him. When the man had walked all

the way to the sea, the djinn waited for nightfall and then showed him

eight falling stars in the northern sky. To each falling star, Al-faq

gave a name.

"Remember," said the djinn. "Never speak. Never look for them."

The man's face was wet with tears. He nodded.

"Keep faith with me always, no matter what."

The man nodded again and smiled wearily. He made a gesture of gratitude,

of blessing.

"No, do not bless me," said Al-faq. "I am not worthy."

At the nearest village, the djinn went from house to house and whispered

in the ears of many sleepers: "There is a holy man beside the sea. Find

him. Care for him."

Then the djinn Al-faq, who perhaps is a faithful djinn and perhaps is

not, returned to the crack between night and day. And if the world has

not yet ended, he lives there still.

Bruce Holland Rogers

- - - - - - - - - - T O P - - - - - - - - - -

Egaeus is my name. My family - I will not name it -

is one of the oldest in the land. We have lived here, inside the walls

of this great house, for many hundreds of years. I sometimes walk

through its silent rooms. Each one is richly decorated, by the hands of

only the finest workmen. But my favorite has always been the library. It

is there, among books, that I have always spent most of my time.

My mother died in the library; I was born here. Yes, the world heard my

first cries here; and these walls, the books that stand along them are

among the first things I can remember in my life.

I was born here in this room, but my life did not begin here. I know I

lived another life before the one I am living now. I can remember

another time, like a dream without shape or body; a world of eyes, sweet

sad sounds and silent shadows. I woke up from that long night, my eyes

opened, and I saw the light of day again - here in this room full of

thoughts and dreams.

As a child, I spent my days reading in this library, and my young sdays

dreaming here. The years passed, I grew up without noticing it, and soon

I found that I was no longer young. I was already in the middle of my

life, and I was still living here in the house of my fathers.

I almost never left the house, and I left the library less and less. And

so, slowly, the real world - life in the world outside these walls -

began to seem like a dream for me. The wild ideas, the dreams inside

my head were my real world. They were my whole life.

Berenice and I were cousins. She and I grew up

together here in this house. But we grew so differently. I was the weak

one, so often sick, always lost in my dark and heavy thoughts. She was

the strong, healthy one, always so full of life, always shining like a

bright new sun. She ran over the hills under the great blue sky while I

studied in the library. I lived inside the walls of my mind, fighting

with the most difficult and painful ideas. She walked quickly and

happily through life, never thinking of the shadows around her. I

watched our young years flying away on the silent wings of time.

Berenice never thought of tomorrow. She lived only for the day.

Berenice – I call out her name c- Berenice! And a thousand sweet voices

answer me from the past. I can see her clearly now, as she was in her

early days of beauty and light. I see her … and then suddenly all is

darkness, mystery and fear.

Her bright young days ended when an illness – a terrible illness – came

down on her like a sudden storm. I watched the dark clouds pass over

her. I saw it change her body and mind completely. The cloud came and

went, leaving someone I did not know. Who was this sad person I saw now?

Where was my Berenice, the Berenice I once knew?

This first illness caused several other illnesses to follow. One of

these was a very unusual type of epilepsy. This epilepsy always came

suddenly, without warning. Suddenly, her mind stopped working. She fell

to the ground, red in the face, shaking all over, making strange sounds,

her eyes not seeing any more. The epilepsy often ended with her going

into a kind of very deep sleep. Sometimes, this deep sleep was so deep,

that it was difficult to tell if she was dead or not. Often she woke up

from the sleep as suddenly as the epilepsy began. She would just get up

as if nothing was wrong.

It was during this time that my illness began to get worse. I

felt it growing stronger day by day. I knew I could do nothing to stop

it. And soon, like Berenice, my illness changed my life completely.

It was not only my body that was sick; it was my mind. It was an illness

of the mind. I can only describe it asd a type of monomania (thinking

about one thing, or idea, and not being able to stop).I often lost

myself for hours, deep in thought about something – something so

unimportant that it seemed funny afterwards. But I am afraid it may be

impossible to describe how fully I could lose myself in the useless

study of even the simplest or most ordinary object.

I could sit for hours looking at one letter of a word on a page. I could

stay, for most of a summer’s day, watching a shadow on the floor. I

could sit without taking my eyes off a wood fire in winter, until it

burnt away to nothing. I could sit for a whole night dreaming about the

sweet smell of a flower. I often repeated a single word again and again

for hours until the sound of it had no more meaning for me. When I did

these things, I always lost all idea of myself, all idea of time, of

movement, even of being alive.

There must be no mistake. You must understand that this monomania was

not a kind of dreaming. Dreaming is completely different. The dreamer -

I am talking about the dreamer who is awake, not asleep – needs and uses

the mind to build his dream. Also, the dreamer nearly always forgets

the thought or idea or object that began his dream. But with me, the

object that began the journey into deepest thought always stayed in my

mind. The object was always there at the centre of my thinking. It was

the centre of everything. It was both the subject and the

object of my thoughts. My thoughts always, always came back to

that object in a never-ending circle. The object was no longer real, but

still I could not pull myself away from it!

I never loved Berenice, even during the brightest days of her beauty.

This is because I have never had feelings of the heart. My loves

have always been in the world of the mind.

In the grey light of early morning, among the dancing shadows of the

forest, in the silence of my library at night, Berenice moved quickly

and lightly before my eyes. I never saw Berenice as a living Berenice.

For me, Berenice was a Berenice in a dream. She was not a person of this

world – no, I never thought of her as someone reral. Berenice was the

idea of Berenice. She was something to think about, not someone to

love.

And so why did I feel differently after her illness? Why, when she was

so terribly and sadly changed, did I shake and go white when she came

near me?

Because I saw the terrible waste of that sweet and loving person.

Because now there was nothing left of the Berenice I once knew!

It is true I never loved her. But I knew she always loved me – deeply.

And so, one day – because I felt so sorry for her – I had a

stupid and evil idea. I asked her to marry me.

Our wedding day was growing closer, and one warm afternoon I was sitting

in the library. The clouds were low and dark, the air was heavy,

everything was quiet. Suddenly, lifting my eyes from my book, I saw

Berenice standing in front of me.

She was like a stranger to me, only a weak shadow of the woman I

remembered. I could not even remember how she was before. God, she was

so thin! I could see her arms and legs through the grey clothes that

hung around her wasted body.

She said nothing. And I could not speak. I do not know why, but suddenly

I felt a terrible fear pressing down like a great stone on my heart. I

sat there in my chair, too afraid to move.

Her long hair fell around her face. She was as white as snow. She looked

strangely calm and happy. But there was no life at all in her eyes. They

did not even seem to see me. I watched as her thin, bloodless lips

slowly opened. They made a strange smile that I could not understand.

And it was then that I saw the teeth.

O, why did she have to smile at me! Why did I have to see those teeth?

I heard a door closing and I looked up. Berenice was

not there anymore. The room was empty. But her teeth did not

leave the room of my mind! I now saw them more clearly than when she was

standing in front of me. Every smallest part of each tooth was burnt

into my mind. The teeth! There they were in front of my eyes –

here, there, everywhere I looked. And they were so white, with

her bloodless lips always moving round them!

I tried to fight this sudden, terrible monomania, but it was useless.

All I could think about, all I could see in my mind’s eye was the teeth.

They were now the centre of my life. I held them up in my mind’s eye,

looked at them in every light, turned them every way, I studied their

shapes, their differences; and the more I thought about them, the more I

began to want them. Yes, I wanted them! I had to have the teeth!

Only the teeth could bring me happiness, could stop me from going

mad.

Evening came; then darkness turned into another day; soon a second night

was falling, and I sat there alone, never moving. I was still lost in

thought, in that one same thought: the teeth. I saw them everywhere I

looked – in the evening shadows, in the darkness in front of my eyes.

Then a terrible cry of horror woke me from my dreams. I heard voices,

and more cries of sadness and pain. I got up and opened the door of the

library. A servant girl was standing outside, crying.

‘Your cousin, sir’ she began . ‘It was her epilepsy, sit. She died this

morning.’

This morning? I looked out of the window. Night was falling …

‘We are ready to bury her now, ‘said the girl.

I found myself waking up alone in the library again.

I thought that I could remember unpleasant and excited dreams, but I did

not know what they were. It was midnight.

‘They buried Berenice soon after dark, ‘I told myself again and again.

But I could only half-remember the hours since then – hours full of a

terrible unknown horror.

I knew something happened during the night, but I could not remember

what it was: those hours of the night were like a page of strange

writing that I could not understand.

Next, I heard the high cutting scream of a woman. I remember thinking:

‘What did I do? I asked myself this question out loud. And the walls of

the library answered me in a soft voice like mine: What did you do?

There was a lamp on the table near me, with a small box next to it. I

knew this box well – it belonged to our family’s doctor. But why was it

there, now, on the table? And why was I shaking like a leaf as I looked

at it? Why was my hair standing on my head?

There was a knock on the door. A servant came in. He was wild with fear

and spoke to me quickly, in a low, shaking voice. I could not understand

all of what he was saying.

‘Some of us heard a wild cry during the night, sir’ he said. ‘We went to

find out what it was, and we found Berenice’s body lying in the open,

sir!’ he cried. ‘Someone took her out of the hole where we buried her!

Her body was cut and bleeding! But worse than that, she … she was not

dead, sir! She was still alive!’

He pointed at my clothes. There was blood all over them. I said

nothing.

He took my hand. I saw cuts and dried blood on it. I cried out, jumped

to the table and tried to open the box. I tried and tried but I could

not! It fell to the floor and broke. Dentist’s tools fell out of it, and

with them - so small and so white! – thirty-two teeth fell here, there,

everywhere…

Edgar Allan Poe

From: The Black Cat and other stories

- - - - - - - - - - T O P - - - - - - - - - -

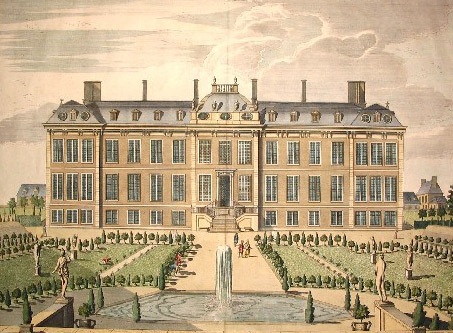

The Field of the forty Steps 1687

One of the mysterious stories about London has its origin on the land

behind the site of the British Museum.

This area is now covered over largely by Senate House and other

University of London buildings. Originally

Montague House was a late 17th-century mansion in

Great Russell Street in the Bloomsbury district, which became the first

home of the British Museum.

The house was actually built twice, both times for the same man, Ralph

Montagu, 1st Duke of Montagu. The late 17th century was Bloomsbury's

most fashionable era, and Montagu purchased a site which is now in the

heart of London. In those days it backed onto the Long Fields. The first

Montague House was designed by the English architect and scientist

Robert Hooke, an architect of moderate ability whose style was

influenced by French planning and Dutch detailing, and was built between

1675 and 1679. Admired by contemporaries, it had a central block and two

service blocks flanking a large courtyard and featured murals by the

Italian artist Antonio Verrio.

In the 17th

century, when

the British Museum was plain Montague House, the land where the

university now stands was open fields, that stretched away to the old

Mary Le Bon Road and the hills beyond. But the fields by Montague House

became legendary after a bizarre duel; a duel that made the fields

famous through thousands of penny dreadfuls sold by itinerant ballad

sellers all over London.

What happened here was a duel, probably fought in 1687 by two brothers,

who were in love with the same girl. The girl sat on a grassy bank and

watched the brothers as they fought to the death...

According to the legend, no grass would grow in the field after the two

brothers died. And ghostly footprints - exactly forty in number - were

regularly seen here for decades afterwards.

Montague House

- - - - - - - - - - T O P - - - - - - - - - -

That

very singular man, old Doctor Heidegger, once invited four venerable

friends to meet him in his study. There were three white-bearded

gentlemen, Mr. Medbourne, Colonel Killigrew, and Mr. Gascoigne, and a

withered gentlewoman whose name was the Widow Wycherley. They were all

melancholy old creatures, who had been unfortunate in life, and whose

greatest misfortune it was that they were not long ago in their graves.

Mr. Medbourne, in the vigor of his age, had been a prosperous merchant,

but had lost his all by a frantic speculation, and was no little better

than a mendicant. Colonel Killigrew had wasted his best years, and his

health and substance, in the pursuit of sinful pleasures, which had

given birth to a brood of pains, such as the gout and divers other

torments of soul and body. Mr. Gascoigne was a ruined politician, a man

of evil fame, or at least had been so, till time had buried him from the

knowledge of the present generation, and made him obscure instead of

infamous. As for the Widow Wycherley, tradition tells us that she was a

great beauty in her day; but, for a long while past, she had lived in

deep seclusion, on account of certain scandalous stories which had

prejudiced the gentry of the town against her. It is a circumstance

worth mentioning that each of these three old gentlemen, Mr. Medbourne,

Colonel Killigrew, and Mr. Gascoigne, were early lovers of the Widow

Wycherley, and had once been on the point of cutting each other's

throats for her sake. And, before proceeding further, I will merely hint

that Doctor Heidegger and all his four guests were sometimes thought to

be a little beside themselves; as is not unfrequently the case with old

people, when worried either by present troubles or woeful recollections.

"My dear friends," said Doctor Heidegger, motioning them to be seated,

"I am desirous of your assistance in one of those little experiments

with which I amuse myself here in my study."

If all stories were true, Doctor Heidegger's study must have been a very

curious place. It was a dim, old-fashioned chamber, festooned with

cobwebs and besprinkled with antique dust. Around the walls stood

several oaken bookcases, the lower shelves of which were filled with

rows of gigantic folios and black-letter quartos, and the upper with

little parchment-covered duodecimos. Over the central bookcase was a

bronze bust of Hippocrates, with which, according to some authorities,

Doctor Heidegger was accustomed to hold consultations in all difficult

cases of his practice. In the obscurest corner of the room stood a tall

and narrow oaken closet, with its door ajar, within which doubtfully

appeared a skeleton. Between two of the bookcases hung a looking-glass,

presenting its high and dusty plate within a tarnished gilt frame. Among

many wonderful stories related of this mirror, it was fabled that the

spirits of all the doctor's deceased patients dwelt within its verge,

and would stare him in the face whenever he looked thitherward. The

opposite side of the chamber was ornamented with the full-length

portrait of a young lady, arrayed in the faded magnificence of silk,

satin, and brocade, and with a visage as faded as her dress. Above half

a century ago Doctor Heidegger had been on the point of marriage with

this young lady; but, being affected with some slight disorder, she had

swallowed one of her lover's prescriptions, and died on the bridal

evening. The greatest curiosity of the study remains to be mentioned; it

was a ponderous folio volume, bound in black leather, with massive

silver clasps. There were no letters on the back, and nobody could tell

the title of the book. But it was well known to be a book of magic; and

once, when a chambermaid had lifted it, merely to brush away the dust,

the skeleton had rattled in its closet, the picture of the young lady

had stepped one foot upon the floor, and several ghastly faces had

peeped forth from the mirror; while the brazen head of Hippocrates

frowned, and said: "Forbear!"

Such was Doctor Heidegger's study. On the summer afternoon of our tale a

small round table, as black as ebony, stood in the centre of the room,

sustaining a cut-glass vase of beautiful form and workmanship. The

sunshine came through the window, between the heavy festoons of two

faded damask curtains, and fell directly across this vase; so that a

mild splendor was reflected from it on the ashen visages of the five old

people who sat around. Four champagne glasses were also on the table.

"My dear old friends," repeated Doctor Heidegger, "may I reckon on your

aid in performing an exceedingly curious experiment?"

Now Doctor Heidegger was a very strange old gentleman, whose

eccentricity had become the nucleus for a thousand fantastic stories.

Some of these fables, to my shame be it spoken, might possibly be traced

back to mine own veracious self; and if any passages of the present tale

should startle the reader's faith, I must be content to bear the stigma

of a fiction-monger.

When the doctor's four guests heard him talk of his proposed experiment,

they anticipated nothing more wonderful than the murder of a mouse in an

air-pump or the examination of a cobweb by the microscope, or some

similar nonsense, with which he was constantly in the habit of pestering

his intimates. But without waiting for a reply, Doctor Heidegger hobbled

across the chamber, and returned with the same ponderous folio, bound in

black leather, which common report affirmed to be a book of magic.

Undoing the silver clasps, he opened the volume, and took from among its

black-letter pages a rose, or what was once a rose, though now the green

leaves and crimson petals had assumed one brownish hue, and the ancient

flower seemed ready to crumble to dust in the doctor's hands.

"This rose," said Doctor Heidegger, with a sigh, "this same withered and

crumbling flower, blossomed five and fifty years ago. It was given me by

Sylvia Ward, whose portrait hangs yonder, and I meant to wear it in my

bosom at our wedding. Five and fifty years it has been treasured between

the leaves of this old volume. Now, would you deem it possible that this

rose of half a century could ever bloom again?"

"Nonsense!" said the Widow Wycherley, with a peevish toss of her head.

"You might as well ask whether an old woman's wrinkled face could ever

bloom again."

"See!" answered Doctor Heidegger.

He uncovered the vase, and threw the faded rose into the water which it

contained. At first, it lay lightly on the surface of the fluid,

appearing to imbibe none of its moisture. Soon, however, a singular

change began to be visible. The crushed and dried petals stirred, and

assumed a deepening tinge of crimson, as if the flower were reviving

from a death-like slumber; the slender stalk and twigs of foliage became

green; and there was the rose of half a century, looking as fresh as

when Sylvia Ward had first given it to her lover. It was scarcely full

blown; for some of its delicate red leaves curled modestly around its

moist bosom, within which two or three dewdrops were sparkling.

"That is certainly a very pretty deception," said the doctor's friends;

careless, however, for they had witnessed greater miracles at a

conjurer's show; "pray how was it effected?"

"Did you ever hear of the 'Fountain of Youth,'" asked Doctor Heidegger,

"which Ponce de Leon, the Spanish adventurer, went in search of, two or

three centuries ago?"

"But did Ponce de Leon ever find it?" said the Widow Wycherley.

"No," answered Doctor Heidegger, "for he never sought it in the right

place. The famous Fountain of Youth, if I am rightly informed, is

situated in the southern part of the Floridian peninsula, not far from

Lake Macaco. Its source is overshadowed by several magnolias, which,

though numberless centuries old, have been kept as fresh as violets, by

the virtues of this wonderful water. An acquaintance of mine, knowing my

curiosity in such matters, has sent me what you see in the vase."

"Ahem!" said Colonel Killigrew, who believed not a word of the doctor's

story; "and what may be the effect of this fluid on the human frame?"

"You shall judge for yourself, my dear Colonel," replied Doctor

Heidegger; "and all of you, my respected friends, are welcome to so much

of this admirable fluid as may restore to you the bloom of youth. For my

own part, having had much trouble in growing old, I am in no hurry to

grow young again. With your permission, therefore, I will merely watch

the progress of the experiment."

While he spoke, Doctor Heidegger had been filling the four champagne

glasses with the water of the Fountain of Youth. It was apparently

impregnated with an effervescent gas; for little bubbles were

continually ascending from the depths of the glasses, and bursting in

silvery spray at the surface. As the liquor diffused a pleasant perfume,

the old people doubted now that it possessed cordial and comfortable

properties; and though utter sceptics as to its rejuvenescent power,

they were inclined to swallow it at once. But Doctor Heidegger besought

them to stay a moment.

"Before you drink, my respectable old friends," said he, "it would be

well that, with the experience of a lifetime to direct you, you should

draw up a few general rules for your guidance, in passing a second time

through the perils of youth. Think what a sin and shame it would be if,

with your peculiar advantages, you should not become patterns of virtue

and wisdom to all the young people of the age!"

The doctor's four venerable friends made him no answer, except by a

feeble and tremulous laugh; so very ridiculous was the idea that,

knowing how closely repentance treads behind the steps of error, they

should ever go astray again.

"Drink, then," said the doctor, bowing: "I rejoice that I have so well

selected the subjects of my experiment."

With palsied hands they raised the glasses to their lips. The liquor, if

it really possessed such virtues as Doctor Heidegger imputed to it,

could not have been bestowed on four human beings who needed it more

woefully. They looked as if they had never known what youth or pleasure

was, but had been the offspring of nature's dotage, and always the gray,

decrepit, sapless, miserable creatures, who now sat stooping round the

doctor's table, without life enough in their souls or bodies to be

animated even by the prospect of growing young again. They drank off the

water, and replaced their glasses on the table.

Assuredly there was an almost immediate improvement in the aspect of the

party, not unlike what might have been produced by a glass of generous

wine, together with a sudden glow of cheerful sunshine, brightening over

all their visages at once. There was a healthful suffusion on their

cheeks, instead of the ashen hue that had made them look so corpselike.

They gazed at one another, and fancied that some magic power had really

begun to smooth away the deep and sad inscriptions which Father Time had

been so long engraving on their brows. The Widow Wycherley adjusted her

cap, for she felt almost like a woman again.

"Give us more of this wondrous water!" cried they, eagerly. "We are

younger--but we are still too old! Quick--give us more!"

"Patience! patience!" quoth Doctor Heidegger, who sat watching the

experiment with philosophic coolness. "You have been a long time growing

old. Surely you might be content to grow young in half an hour! But the

water is at your service."

Again he filled their glasses with the liquor of youth, enough of which

still remained in the vase to turn half the old people in the city to

the age of their own grandchildren. While the bubbles were yet sparkling

on the brim, the doctor's four guests snatched their glasses from the

table, and swallowed the contents at a single gulp. Was it delusion?

Even while the draught was passing down their throats it seemed to have

wrought a change on their whole systems. Their eyes grew clear and

bright; a dark shade deepened among their silvery locks; they sat round

the table, three gentlemen of middle age, and a woman hardly beyond her

buxom prime.

"My dear widow, you are charming!" cried Colonel Killigrew, whose eyes

had been fixed upon her face, while the shadows of age were flitting

from it like darkness from the crimson daybreak.

The fair widow knew of old that Colonel Killigrew's compliments were not

always measured by sober truth; so she started up and ran to the mirror,

still dreading that the ugly visage of an old woman would meet her gaze.

Meanwhile the three gentlemen behaved in such a manner as proved that

the water of the Fountain of Youth possessed some intoxicating

qualities, unless, indeed, their exhilaration of spirits were merely a

lightsome dizziness, caused by the sudden removal of the weight of

years. Mr. Gascoigne's mind seemed to run on political topics, but

whether relating to the past, present, or future could not easily be

determined, since the same ideas and phrases have been in vogue these

fifty years. Now he rattled forth full-throated sentences about

patriotism, national glory, and the people's rights; now he muttered

some perilous stuff or other, in a sly and doubtful whisper, so

cautiously that even his own conscience could scarcely catch the secret;

and now, again, he spoke in measured accents and a deeply deferential

tone, as if a royal ear were listening to his well-turned periods.

Colonel Killigrew all this time had been trolling forth a jolly

battle-song, and ringing his glass toward the buxom figure of the Widow

Wycherley. On the other side of the table Mr. Medbourne was involved in

a calculation of dollars and cents, with which was strangely

intermingled a project for supplying the East Indies with ice, by

harnessing a team of whales to the polar icebergs.

As for the Widow Wycherley, she stood before the mirror, courtesying and

simpering to her own image, and greeting it as the friend whom she loved

better than all the world beside. She thrust her face close to the glass

to see whether some long-remembered wrinkle or crow's-foot had indeed

vanished. She examined whether the snow had so entirely melted from her

hair that the venerable cap could be safely thrown aside. At last,

turning briskly away, she came with a sort of dancing step to the table.

"My dear old doctor," cried she, "pray favor me with another glass!"

"Certainly, my dear madam, certainly!" replied the complaisant doctor.

"See! I have already filled the glasses."

There, in fact, stood the four glasses, brimful of this wonderful water,

the delicate spray of which, as it effervesced from the surface,

resembled the tremulous glitter of diamonds. It was now so nearly sunset

that the chamber had grown duskier than ever; but a mild and moon-like

splendor gleamed from within the vase, and rested alike on the four

guests, and on the doctor's venerable figure. He sat in a high-backed,

elaborately carved oaken chair, with a gray dignity of aspect that might

have well befitted that very Father Time, whose power had never been

disputed, save by this fortunate company. Even while quaffing the third

draught of the Fountain of Youth, they were almost awed by the

expression of his mysterious visage.

But the next moment the exhilarating gush of young life shot through

their veins. They were now in the happy prime of youth. Age, with its

miserable train of cares, and sorrows, and diseases, was remembered only

as the trouble of a dream, from which they had joyously awoke. The fresh

gloss of the soul, so early lost, and without which the world's

successive scenes had been but a gallery of faded pictures, again threw

its enchantment over all their prospects. They felt like new-created

beings in a new-created universe.

"We are young! We are young!" they cried, exultingly.

Youth, like the extremity of age, had effaced the strongly marked

characteristics of middle life, and mutually assimilated them all. They

were a group of merry youngsters, almost maddened with the exuberant

frolicsomeness of their years. The most singular effect of their gayety

was an impulse to mock the infirmity and decrepitude of which they had

so lately been the victims. They laughed loudly at their old-fashioned

attire--the wide-skirted coats and flapped waistcoats of the young men,

and the ancient cap and gown of the blooming girl. One limped across the

floor like a gouty grandfather; one set a pair of spectacles astride of

his nose, and pretended to pore over the black-letter pages of the book

of magic; a third seated himself in an arm-chair, and strove to imitate

the venerable dignity of Doctor Heidegger. Then all shouted mirthfully,

and leaped about the room. The Widow Wycherley--if so fresh a damsel

could be called a widow--tripped up to the doctor's chair with a

mischievous merriment in her rosy face.

"Doctor, you dear old soul," cried she, "get up and dance with me!" And

then the four young people laughed louder than ever, to think what a

queer figure the poor old doctor would cut.

"Pray excuse me," answered the doctor, quietly. "I am old and rheumatic,

and my dancing days were over long ago. But either of these gay young

gentlemen will be glad of so pretty a partner."

"Dance with me, Clara!" cried Colonel Killigrew.

"She promised me her hand fifty years ago!" exclaimed Mr. Medbourne.

They all gathered round her. One caught both her hands in his passionate

grasp--another threw his arm about her waist--the third buried his hand

among the curls that clustered beneath the widow's cap. Blushing,

panting, struggling, chiding, laughing, her warm breath fanning each of

their faces by turns, she strove to disengage herself, yet still

remained in their triple embrace. Never was there a livelier picture of

youthful rivalship, with bewitching beauty for the prize. Yet, by a

strange deception, owing to the duskiness of the chamber and the antique

dresses which they still wore, the tall mirror is said to have reflected

the figures of the three old, gray, withered grand-sires, ridiculously

contending for the skinny ugliness of a shrivelled grandam.

But they were young: their burning passions proved them so. Inflamed to

madness by the coquetry of the girl-widow, who neither granted nor quite

withheld her favors, the three rivals began to interchange threatening

glances. Still keeping hold of the fair prize, they grappled fiercely at

one another's throats. As they struggled to and fro, the table was

overturned, and the vase dashed into a thousand fragments. The precious

Water of Youth flowed in a bright stream across the floor, moistening

the wings of a butterfly, which, grown old in the decline of summer, had

alighted there to die. The insect fluttered lightly through the chamber,

and settled on the snowy head of Doctor Heidegger.

"Come, come, gentlemen!--come, Madame Wycherley!" exclaimed the doctor,

"I really must protest against this riot."

They stood still and shivered; for it seemed as if gray Time were

calling them back from their sunny youth, far down into the chill and

darksome vale of years. They looked at old Doctor Heidegger, who sat in

his carved arm-chair, holding the rose of half a century which he had

rescued from among the fragments of the shattered vase. At the motion of

his hand the rioters resumed their seats, the more readily because their

violent exertions had wearied them, youthful though they were.

"My poor Sylvia's rose!" ejaculated Doctor Heidegger, holding it in the

light of the sunset clouds; "it appears to be fading again."

And so it was. Even while the party were looking at it the flower

continued to shrivel up, till it became as dry and fragile as when the

doctor had first thrown it into the vase. He shook off the few drops of

moisture which clung to its petals.

"I love it as well thus as in its dewy freshness," observed he, pressing

the withered rose to his withered lips. While he spoke, the butterfly

fluttered down from the doctor's snowy head, and fell upon the floor.

His guests shivered again. A strange dullness, whether of the body or

spirit they could not tell, was creeping gradually over them all. They

gazed at one another, and fancied that each fleeting moment snatched

away a charm, and left a deepening furrow where none had been before.

Was it an illusion? Had the changes of a lifetime been crowded into so

brief a space, and were they now four aged people, sitting with their

old friend, Doctor Heidegger?

"Are we grown old again so soon?" cried they, dolefully.

In truth, they had. The Water of Youth possessed merely a virtue more

transient than that of wine. The delirium which it created had

effervesced away. Yes, they were old again! With a shuddering impulse,

that showed her a woman still, the widow clasped her skinny hands over

her face, and wished that the coffin lid were over it, since it could be

no longer beautiful.

"Yes, friends, ye are old again," said Doctor Heidegger; "and lo! the

Water of Youth is all lavished on the ground. Well, I bemoan it not; for

if the fountain gushed at my doorstep, I would not stoop to bathe my

lips in it--no, though its delirium were for years instead of moments.

Such is the lesson ye have taught me!"

But the doctor's four friends had taught no such lesson to themselves.

They resolved forthwith to make a pilgrimage to Florida, and quaff at

morning, noon, and night from the Fountain of Youth.

Nathaniel Hawthorne

- - - - - - - - - - T O P - - - - - - - - - -

It's now quite common in London

to see geese flying overhead or swans; even, occasionally, a rarity such

as a cormorant. Along the Thames right into the heart of the city herons

now stalk the shallows and various wildlife bodies tell us that owls

roost in Parliament Square while kestrels hover above the Commercial

Road.

In the nineteenth century things were very different, as pollution

caused by millions of coal fires - not to mention heavy industry - meant

there was far less wildlife than today.

But having said that, London’s bigger parks have always provided a haven

for wildlife, which is why reports of ducks wandering across Kensington

High Street with their ducklings coming along behind were always quite

common.

Far less common was the bizarre wildlife encounter in Kensington

reported in an Victorian newspaper.

Miss Charlotte Wadham, a young and attractive violinist, was walking

home one autumn evening after what the delightfully old-fashioned

newspaper reporter described as 'a musical engagement involving the

celebrated Mr. Bach'. She was halfway up Kensington Church Street when

she was struck by what she later described to the newspaper as 'a

terrific blow to the side of the head'. In fact the bump was so hard

that she was knocked unconscious for a few moments.

One of the witnesses who helped the injured woman into a local house

where brandy was administered (much, apparently, to the delight of Miss

Wadham) described an extraordinary circumstance that almost certainly

accounted for the knockout blow. When the witness had run up to the

prostrate Miss Wadham he spotted a large fish lying on the pavement

nearby,. Being a fisherman he knew that this was not the sort of fish

one buys at the fishmonger. It was in fact a roach, a common British

freshwater fish, but completely inedible. The witness told the newspaper

that at first he could not understand how the fish came to be lying in

the street, but in helping the injured woman to her feet, he noticed

something very odd indeed. The woman's head and the shoulder of her coat

were dusted here and there with fish scales. The scales were without

question from the dead roach found at the scene.

When the newspaper reporter compiled his report on the incident he

quoted a professor of zoology who stated that Miss Wadham was almost

certainly felled by a roach dropped by a passing bird, possibly a heron

or cormorant.

Miss Wadham's

violin, much to her relief, was unharmed.

From: London's strangest tales, Tom Quinn

- - - - - - - - - - T O P - - - - - - - - - -

The Origin of Tis Lake

Denmark

A troll had once taken up his abode near the village of Kund, in the high bank on which the church now stands; but when the people about there had become pious, and went constantly to church, the troll was dreadfully annoyed by their almost incessant ringing of bells in the steeple of the church. He was at last obliged, in consequence of it, to take his departure; for nothing has more contributed to the emigration of the troll folk out of the country than the increasing piety of the people, and their taking to bell ringing. The troll of Kund accordingly quitted the country, and went over to Funen, where he lived for some time in peace and quiet.

Now it chanced that a man who had lately settled in the town of Kund, coming to Funen on business, met on the road with this same troll. "Where do you live?" said the troll to him.

Now there was nothing whatever about the troll unlike a man, so he answered him, as was the truth, "I am from the town of Kund."

"So?" said the troll. "I don't know you then! And yet I think I know every man in Kund. Will you, however," continued he, "just be so kind to take a letter from me back with you to Kund?"

The man said, of course, he had no objection. The troll then thrust the letter into his pocket, and charged him strictly not to take it out till he came to Kund church, and then to throw it over the churchyard wall, and the person for whom it was intended would get it.

The troll then went away in great haste, and with him the letter went entirely out of the man's mind. But when he was come back to Zealand he sat down by the meadow where Tis Lake now is, and suddenly recollected the troll's letter. He felt a great desire to look at it at least. So he took it out of his pocket, and sat a while with it in his hands, when suddenly there began to dribble a little water out of the seal. The letter now unfolded itself, and the water came out faster and faster, and it was with the utmost difficulty that the poor man was enabled to save his life, for the malicious troll had enclosed an entire lake in the letter.

The troll, it is plain, had thought to avenge himself on Kund church by destroying it in this manner; but God ordered it so that the lake chanced to run out in the great meadow where it now flows.

Source: Thomas Keightley, The Fairy Mythology (London: H. G. Bohn, 1850), pp. 111-112.

- - - - - - - - - - T O P - - - - - - - - - -

Who goes there?"

No answer. The watchman sees nothing, but through the roar of the wind

and the trees distinctly hears someone walking along the avenue ahead of

him. A March night, cloudy and foggy, envelopes the earth, and it seems

to the watchman that the earth, the sky, and he himself with his

thoughts are all merged together into something vast and impenetrably

black. He can only grope his way.

"Who goes there?" the watchman repeats, and he begins to fancy that he

hears whispering and smothered laughter. "Who's there?"

"It's I, friend . . ." answers an old man's voice.

"But who are you?"

"I . . . a traveller."

"What sort of traveller?" the watchman cries angrily, trying to disguise

his terror by shouting. "What the devil do you want here? You go

prowling about the graveyard at night, you ruffian!"

"You don't say it's a graveyard here?"

"Why, what else? Of course it's the graveyard! Don't you see it is?"

"O-o-oh . . . Queen of Heaven!" there is a sound of an old man sighing.

"I see nothing, my good soul, nothing. Oh the darkness, the darkness!

You can't see your hand before your face, it is dark, friend. O-o-oh. .

."

"But who are you?"

"I am a pilgrim, friend, a wandering man."

"The devils, the nightbirds. . . . Nice sort of pilgrims! They are

drunkards . . ." mutters the watchman, reassured by the tone and sighs

of the stranger. "One's tempted to sin by you. They drink the day away

and prowl about at night. But I fancy I heard you were not alone; it

sounded like two or three of you."

"I am alone, friend, alone. Quite alone. O-o-oh our sins. . . ."

The watchman stumbles up against the man and stops.

"How did you get here?" he asks.

"I have lost my way, good man. I was walking to the Mitrievsky Mill and

I lost my way."

"Whew! Is this the road to Mitrievsky Mill? You sheepshead! For the

Mitrievsky Mill you must keep much more to the left, straight out of the

town along the high road. You have been drinking and have gone a couple

of miles out of your way. You must have had a drop in the town."

"I did, friend . . . Truly I did; I won't hide my sins. But how am I to

go now?"

"Go straight on and on along this avenue till you can go no farther, and

then turn at once to the left and go till you have crossed the whole

graveyard right to the gate. There will be a gate there. . . . Open it

and go with God's blessing. Mind you don't fall into the ditch. And when

you are out of the graveyard you go all the way by the fields till you

come out on the main road."

"God give you health, friend. May the Queen of Heaven save you and have

mercy on you. You might take me along, good man! Be merciful! Lead me to

the gate."

"As though I had the time to waste! Go by yourself!"

"Be merciful! I'll pray for you. I can't see anything; one can't see

one's hand before one's face, friend. . . . It's so dark, so dark! Show

me the way, sir!"

"As though I had the time to take you about; if I were to play the nurse

to everyone I should never have done."

"For Christ's sake, take me! I can't see, and I am afraid to go alone

through the graveyard. It's terrifying, friend, it's terrifying; I am

afraid, good man."

"There's no getting rid of you," sighs the watchman. "All right then,

come along."

The watchman and the traveller go on together. They walk shoulder to

shoulder in silence. A damp, cutting wind blows straight into their

faces and the unseen trees murmuring and rustling scatter big drops upon

them. . . . The path is almost entirely covered with puddles.

"There is one thing passes my understanding," says the watchman after a

prolonged silence -- "how you got here. The gate's locked. Did you climb

over the wall? If you did climb over the wall, that's the last thing you

would expect of an old man."

"I don't know, friend, I don't know. I can't say myself how I got here.

It's a visitation. A chastisement of the Lord. Truly a visitation, the

evil one confounded me. So you are a watchman here, friend?" |

"Yes."

"The only one for the whole graveyard?"

There is such a violent gust of wind that both stop for a minute.

Waiting till the violence of the wind abates, the watchman answers:

"There are three of us, but one is lying ill in a fever and the other's

asleep. He and I take turns about."

"Ah, to be sure, friend. What a wind! The dead must hear it! It howls

like a wild beast! O-o-oh."

"And where do you come from?"

"From a distance, friend. I am from Vologda, a long way off. I go from

one holy place to another and pray for people. Save me and have mercy

upon me, O Lord."

The watchman stops for a minute to light his pipe. He stoops down behind

the traveller's back and lights several matches. The gleam of the first

match lights up for one instant a bit of the avenue on the right, a

white tombstone with an angel, and a dark cross; the light of the second

match, flaring up brightly and extinguished by the wind, flashes like

lightning on the left side, and from the darkness nothing stands out but

the angle of some sort of trellis; the third match throws light to right

and to left, revealing the white tombstone, the dark cross, and the

trellis round a child's grave. "The departed sleep; the dear ones

sleep!" the stranger mutters, sighing loudly. "They all sleep alike,

rich and poor, wise and foolish, good and wicked. They are of the same

value now. And they will sleep till the last trump. The Kingdom of

Heaven and peace eternal be theirs."

"Here we are walking along now, but the time will come when we shall be

lying here ourselves," says the watchman.

"To be sure, to be sure, we shall all. There is no man who will not die.

O-o-oh. Our doings are wicked, our thoughts are deceitful! Sins, sins!

My soul accursed, ever covetous, my belly greedy and lustful! I have

angered the Lord and there is no salvation for me in this world and the

next. I am deep in sins like a worm in the earth."

"Yes, and you have to die."

"You are right there."

"Death is easier for a pilgrim than for fellows like us," says the

watchman.

"There are pilgrims of different sorts. There are the real ones who are

God-fearing men and watch over their own souls, and there are such as

stray about the graveyard at night and are a delight to the devils. . .

Ye-es! There's one who is a pilgrim could give you a crack on the pate

with an axe if he liked and knock the breath out of you." "What are you

talking like that for?"

"Oh, nothing . . . Why, I fancy here's the gate. Yes, it is. Open it,

good man.

The watchman, feeling his way, opens the gate, leads the pilgrim out by

the sleeve, and says: "Here's the end of the graveyard. Now you must

keep on through the open fields till you get to the main road. Only

close here there will be the boundary ditch -- don't fall in. . . . And

when you come out on to the road, turn to the right, and keep on till

you reach the mill. . . ."

"O-o-oh!" sighs the pilgrim after a pause, "and now I am thinking that I

have no cause to go to Mitrievsky Mill. . . . Why the devil should I go

there? I had better stay a bit with you here, sir. . . ."

"What do you want to stay with me for?"

"Oh . . . it's merrier with you! . . . ."

"So you've found a merry companion, have you? You, pilgrim, are fond of

a joke I see. . . ."

"To be sure I am," says the stranger, with a hoarse chuckle. "Ah, my

dear good man, I bet you will remember the pilgrim many a long year!"

"Why should I remember you?"

"Why I've got round you so smartly. . . . Am I a pilgrim? I am not a

pilgrim at all." "What are you then?"

"A dead man. . . . I've only just got out of my coffin. . . . Do you

remember Gubaryev, the locksmith, who hanged himself in carnival week?

Well, I am Gubaryev himself! . . ."

"Tell us something else!"

The watchman does not believe him, but he feels all over such a cold,

oppressive terror that he starts off and begins hurriedly feeling for

the gate.

"Stop, where are you off to?" says the stranger, clutching him by the

arm. "Aie, aie, aie . . . what a fellow you are! How can you leave me

all alone?"

"Let go!" cries the watchman, trying to pull his arm away.

"Sto-op! I bid you stop and you stop. Don't struggle, you dirty dog! If

you want to stay among the living, stop and hold your tongue till I tell

you. It's only that I don't care to spill blood or you would have been a

dead man long ago, you scurvy rascal. . . . Stop!"

The watchman's knees give way under him. In his terror he shuts his

eyes, and trembling all over huddles close to the wall. He would like to

call out, but he knows his cries would not reach any living thing. The

stranger stands beside him and holds him by the arm. . . . Three minutes

pass in silence.

"One's in a fever, another's asleep, and the third is seeing pilgrims on

their way," mutters the stranger. "Capital watchmen, they are worth

their salary! Ye-es, brother, thieves have always been cleverer than

watchmen! Stand still, don't stir. . . ."

Five minutes, ten minutes pass in silence. All at once the wind brings

the sound of a whistle.

"Well, now you can go," says the stranger, releasing the watchman's arm.

"Go and thank God you are alive!"

The stranger gives a whistle too, runs away from the gate, and the

watchman hears him leap over the ditch.

With a foreboding of something very dreadful in his heart, the watchman,

still trembling with terror, opens the gate irresolutely and runs back

with his eyes shut. At the turning into the main avenue he hears hurried

footsteps, and someone asks him, in a hissing voice: "Is that you,

Timofey? Where is Mitka?"

And after running the whole length of the main avenue he notices a

little dim light in the darkness. The nearer he gets to the light the

more frightened he is and the stronger his foreboding of evil.

"It looks as though the light were in the church," he thinks. "And how

can it have come there? Save me and have mercy on me, Queen of Heaven!

And that it is."

The watchman stands for a minute before the broken window and looks with

horror towards the altar. . . . A little wax candle which the thieves

had forgotten to put out flickers in the wind that bursts in at the

window and throws dim red patches of light on the vestments flung about

and a cupboard overturned on the floor, on numerous footprints near the

high altar and the altar of offerings.

A little time passes and the howling wind sends floating over the

churchyard the hurried uneven clangs of the alarm-bell. . . .

Anton Chekhov

- - - - - - - - - - T O P - - - - - - - - - -

We invite you to send more stories to cedars@live.nl, mentioning 'stories'. Will you please add the source?

![]()

![]()

Texts, pictures,

etc. are the property of their respective owners.

Cedar Gallery is a non-profit site. All works and articles are published

on this site purely for educational reasons, for the purpose of

information and with good intentions. If the legal representatives ask

us to remove a text or picture from the site, this will be done

immediately. We guarantee to fulfill such demands within 72 hours.

(Cedar Gallery reserves the right to investigate whether the person

submitting that demand is authorized to do so or not).

The contents of this website (texts, pictures and other material) are protected by copyright. You are welcome to visit the site and enjoy it, but you are not allowed to use it, copy it, spread it. If you like to use a picture or text, first send your request to